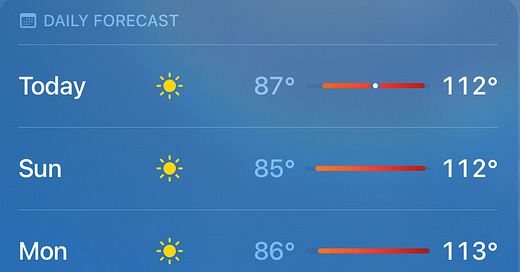

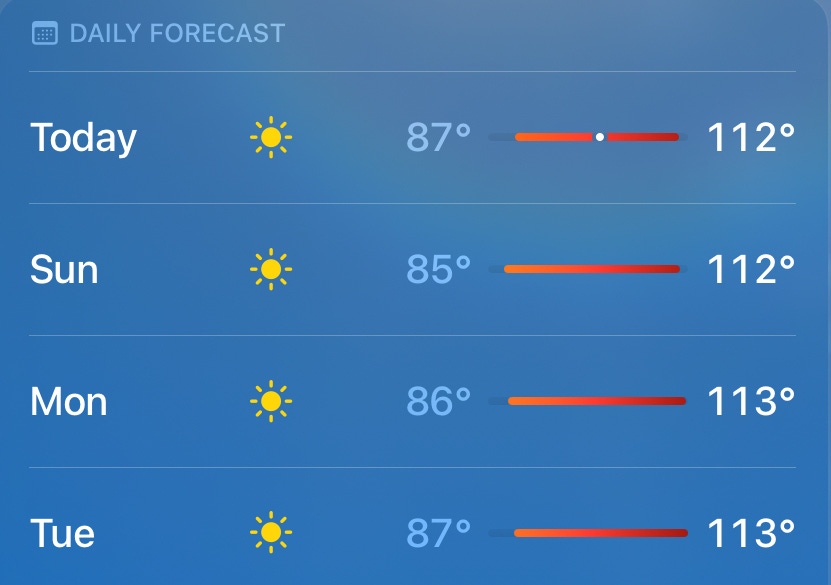

After an unusually mild and rainy June, a bit of monsoon come early, it got up over 110°F (43°C) here in the Phoenix Valley this week. That’s past the threshold where standing in the shade no longer offers much relief, where a breeze starts feeling like a hot hairdryer to the face. You walk outside and you just feel blasted. It’s uncomfortable, exhausting, and dangerous.

If you follow the r/Phoenix subreddit, you’ll see that a particular type of article comes out every summer: some east-coaster flagellates themselves by trying to walk a couple miles in the Valley’s summer heat, and then bemoans the millions choosing to live here as a project of pure hubris.

This year it was The Atlantic, which published a 25,000(!) word piece by George Packer titled, ominously, “What Will Become of American Civilization?” It’s an extensive look at Phoenix and the Valley — its history, its heat and its water, its role as both America’s fastest growing city and the perceived central battleground in our nation’s lukewarm cultural-political civil war.

Perhaps you’d expect that I, as a Phoenix resident who frequently writes about climate futures and their intersection with the American soul, would be the ideal target for such a piece. In truth, my friends and I read Packer’s critique with a certain frustration. Not because the reporting was bad; it was often illuminating.1

No, I disliked the piece because it paints a picture of Phoenix as this uniquely troubled place, when an equivalent essay could be written about pretty much any major city in the country. The climate catastrophe is coming for everyone. Politics is poisoned everywhere. (Just look at this weirdness in Vermont.) The homelessness crisis is a nationwide phenomenon, one that flows from the general arrangement of class power and not just from any one city’s policy choices. Early on in the article Packer says “New Yorkers and Chicagoans don’t wonder how long their cities will go on existing.” But why not? It seems to me they should.

I’m not exactly trying to cape for Phoenix here. There is indeed a lot wrong with this place, and we are indeed on the front lines of both the climate and political crises. But takes that look askance at Phoenix’s dependance on air conditioning during the summer never seem to turn a similar critical lens on cities that rely on gas heating in every building to be habitable during the winter.

I’ve seen so much of this double standard in the last couple years — New Yorkers and Canadians and Swedes all asking how I can bear to live in Arizona or how long Phoenix will last — that I’ve had to coin a term for it: “thermochauvinism.”

Thermochauvinism is the (often unconscious) assumption that it’s reasonable to live in cold places but unreasonable to live in hot ones. Thermochauvinism doesn’t blink at the massive infrastructure investments required to keep much of the Global North functioning through the coldest months of the year: gas heating, snow removal, salting of roads and sidewalks, winter clothes for every citizen, hand warmers, engine warmers, antifreeze, snow days, etc. etc. And yet similar investments in cooling somehow constitute a moral failing.

There is something Eurocentric, colonialist, even quasi-racist about thermochauvinism. Brown and Black people live in warmer places, and are then depicted as lazy or uncivilized for the ways they adapt to the heat. White people live in cooler place and are thought to be industrious for adapting to the cold. A siesta or a dip in the river is a primal throwback, while hygge is advanced cultural technology. People who head north to escape hot summers are labeled ‘climate refugees’, while people who head south to escape cold winters are ‘snowbirds.’

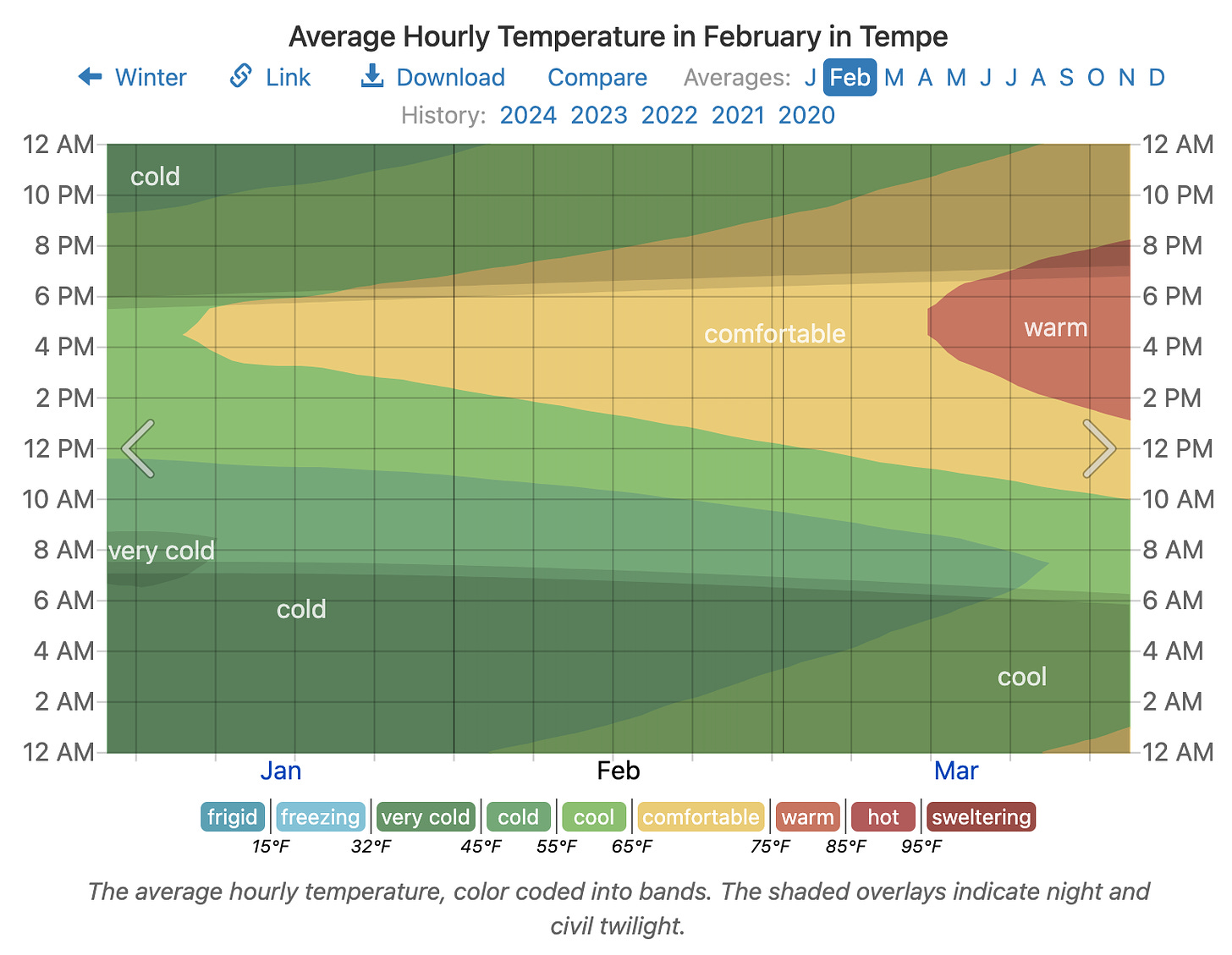

Thermochauvinism also includes the assumption that summer is for enjoying oneself outside, while winter is for staying indoors — when in places like Phoenix it’s exactly the opposite. C and I have taken to calling this season “hot winter”: a time for staying cool and cozy in air conditioned spaces, writing and reading and playing games, venturing out for excursions to museums or libraries, and generally waiting for Our Great Enemy The Sun to lose its grip on the land. November through April, on the other hand, are precious months best spent hiking, camping, lazing in hammocks, drinking on patios, playing basketball or lawn sports, gardening, taking long walks in the park with friends, and so on.

One of the most brain-bending experiences I’ve had in recent memory was spending last summer in northern Sweden. In Luleå, winters and frigid and dark while summers are balmy and endlessly bright. We slept like babies in February, but come June the midnight sun kept us up, as did the general bustle of activity around town. Swedes there are very practiced at living with a great deal of seasonality — shifting their behavior and norms based on the time of year and accompanying weather. We had not been trained in their rhythms, and so found them dislocating.

As climate becomes a more dominant force in shaping our lives, I think we will need to get more thoughtful about seasonality, which for the majority of human history has been a dominant force in culture and social structures. But we have to do so without defaulting to a long-gone European norm, which means it’s time to ditch thermochauvinism.

Yes, Phoenix is getting harsher, even deadlier during the summer, no question. But it also still has, for about six months, the nicest weather in North America. I know you’re going to say California, but I’ve lived in California, and from Halloween to May Day I’ll take Phoenix every time.

Despite the flood of east-coaster think pieces, I think there’s an argument to be made that Phoenix is well-positioned to thrive in the climate crisis. While we predictably have extremely hot summers, we’ve so far been much less vulnerable to the various heavy weather calamities that are increasingly battering the rest of the country: sea level rise, super-charged hurricanes, gigafloods, tornado outbreaks, megafires and attendant smoke crises, polar vortex freeze-overs, et al. In many northern cities air conditioning is a rarity in older buildings, leaving millions scrambling to deal to each year’s new round of record-breaking, greenhouse-juiced heatwaves. Here every building comes with A/C, and the power grid is built to handle the summer load, putting Phoenix weirdly ahead of the curve on climate adaption. Once you realize all that, it’s no wonder people are flocking to live here.

From an energetic perspective, thermochauvinism makes no sense. Per capita it takes more energy to heat Minneapolis in the winter than to cool Phoenix in the summer. This is because raising temperatures simply uses more energy than lowering them. Our cooling technologies are surprisingly efficient! And they come pre-electrified. Meanwhile our heating technologies are, frankly, insane. Future people will look at our habit of pumping poisonous gas under every street and into every home the same way we look at the past centuries’ tolerance for tossing human waste out of windows to fester in busy streets.

When it comes to redesigning our civilization around renewable energy, it makes much more sense for people to live in places where the big temperature-based energy needs come during summer days, when sunlight is most abundant, rather than needing that energy on winter nights, when photons are scarce. Some of that is elided by the slight average uptick in the availability of wind power during the winter in many colder places, but in general I think we may find that colder locales require much more energy storage (or non-renewable baseload) compared to hot ones where demand peaks along with supply.

And, last I checked, many more people still die from cold weather than from hot — particularly the homeless. This fact feels weird to write, almost climate-denier adjacent. So, to be clear, planetary heating is the greatest crisis we’ve ever faced, and the imperative to rapidly decarbonize is not in any way blunted by the potential for milder winters or new farm land in Siberia.

But clear thinking about climate change can’t come from a warped assessment of our actual adaptation needs. We have to both do everything in our power to limit and reverse warming, but we also need to learn to roll with the punches that are already here and definitely coming.

Being against thermochauvinism doesn’t mean everyone should leave cold places and move to Phoenix. It means recognizing that we should invest in cooling at least as much (and probably more) than we invest in heating. Because the truth is that the foreseeable future is not about people abandoning cities like Phoenix en masse — it’s about more cities becoming more like Phoenix every year.

What does investing in cooling look like? Well, air conditioning, for one. We can and should build more passive cooling into our homes and cities, and there’s a lot of exciting potential in cooling through heat pumps. But I think it would be prudent for most new buildings to also be built with central air to help deal with extreme heat waves, even in the north. We should also retrofit older buildings as best we can — even if it means my San Francisco friends have to shove an AC box in their beloved bay windows.

We’ll also need to build electrical grids that can handle this new AC load, and the solar energy generation to power them. A lot of environmentalists bemoan the energy costs of AC — something like 10% of emissions, and expected to balloon over the century — but that’s a mindset we need to get over. The quickest way to reduce AC emissions is to put solar panels on rooftops. And, just in general, we are way past the “get a better lightbulb” stage of the energy transition. At this point, it’s on utilities to decarbonize their generation, not on consumers to sweat through dangerous temps for a lower personal energy footprint.

Investing in cooling means not being stingy with cooling centers. If the Twin Cities can have heated bus stops, surely Phoenix should have air conditioned ones — or at least arrangements for transit riders to wait in nearby buildings (we saw this occasionally in Sweden).

It means normalizing and developing cooling clothing and personal cooling devices with the same ingenuity that goes into high tech winter coats, thermal layers, and sleeping bags. I’ve started to see some of these crop up on TikTok, but I suspect there’s a lot of room for innovation in this sector.

It means making sure homes have the equipment to provide access to cold water alongside access to hot. Cold water might not sound like a necessity, but spend a couple months with hot pipes, like we get here in the summer, and I expect you’ll change your mind. (Plus, according to

, cold showers may be a powerful tool in fighting depression.)Investing in cooling means planting a lot of heat-resilient trees up and down every street and even installing shade structures over squares, promenades, and other public gathering places. It means building with cooler materials, particularly when it comes to roads. It means increasing the albedo of every rooftop that isn’t collecting solar energy — something that can hopefully also have globally positive effects on our overall planetary warming.

If we do all this, I think there’s a good chance cities like Phoenix could actually be cooler in 20 years, not hotter. So much of our heat island comes from bad design that we can correct. This isn’t a reason to not fight to cut emissions as fast as possible, to prevent every single hundredth degree of planetary warming we can. But it is a reason to not write off a city of five million people as some kind of failed experiment destined to be abandoned to the desert.

Packer’s Atlantic article is full of interviews critical of growth in the Valley, fretting about new housing and added jobs. “‘The people keep coming, the buildings keep coming, and there’s no long-term solution,’” one quote read, followed by a brief foray into an apocalyptic imaginary of “some future civilization coming upon this place, finding the remains of stucco walls, puzzling over the metal fragments of solar panels, wondering what happened to the people who once lived here.”

The growth in Phoenix and surrounding areas does indeed put pressure on our water supplies. But water is a solvable problem, a matter (like always) of investment. Certainly we should stop letting Saudi-backed alfalfa farms poach our groundwater, and there are reasonable limits to be placed on outer exurban expansion. But Phoenix’s water isn’t running out any time soon. Despite what articles like Packer’s imply, the cities in Arizona aren’t built randomly in the middle of empty desert — they’re built where the water is!

Long term I suspect we’ll be bringing in desalinated seawater from the Gulf of California — a much better use for all that pipeline expertise the fossil fuel industry has developed on its way to roasting our planet. As a rule, I’d rather live in a city like Phoenix that knows it needs to be careful than, say, Johannesburg, where they ran out of water “really slowly, and then all at once.”

But mostly I’m wary of Packer’s “the people keep coming” quote because that’s exactly what the fascists are going to say. Narratives that reduce human beings seeking housing and opportunity to undifferentiated, unthinking masses or consuming, invading hordes — that’s fash language 101. The politics of this century may very well be about overcoming those reactionaries who would prioritize the privileges of existing gentry over the human rights of refugees, migrants, and other newcomers (not to mention the already existing poor and unhoused).

So we need to be very, very careful with language and policy that amounts to “stay away, there’s no more room/water/food/energy.” Instead, we should find ways to make the places where people want or need to go more habitable and welcoming. Not enough housing? Build some. Not enough food? Grow some. Not enough water? Clean some, pump some, pipe some in. Too hot? Invest in cooling. And give the newcomers good jobs helping get these things done. Do not find excuses to turn people away.

Tempe, where I live, is named after a Greek mythological paradise —the city closest to Mount Olympus. We’ve got a world-class university here, and the Valley broadly has great art, great food, great hiking. It’s surrounded by the most biodiverse desert in the world. To deny this because we take our winters in the summer and our summers in the winter is pure thermochauvinism.

I imagine a future with solar panels on every roof and shade sails over every street. In the mornings I’ll write on the patio, fortified by a mister and cold drink. When the summer wind blows hot through the valley, chasing me away from my keyboard, I’ll retreat to the cool inside to continue my work. Or maybe I’ll bike down the tree-lined streets to the public pools that course like canals through the neighborhood. I’ll dip myself in, shedding therms in the water. For the journey home, I wear my clothes wet, the evaporation chilling me as they dry in the desert air. Summers are long, but they do end.

Updates + Miscellany

My Sweden energy stories, along with accompanying art and methodological commentary, have been published as Northern Lights: Four Energy Futures from the North, edited by Anna Krook-Riekkola and Johan Granberg. I expect I’ll have more to say when I get the physical book in hand, but for now just want to point you to the ebook, which is free to download. It’s a lovely, thoughtful project with a great cover and fantastic art.

Last month I mentioned that my “Space Is Dead” essay had been reprinted by a new site publishing non-fiction about SFF, Speculative Insight. Well, SI has pulled together its first batch of essays into both an ebook and a paperback book — quite an interesting collection of writing, imo. You can pick one up here.

My essay last month “The Case for the Butlerian Jihad” neglected to mention that friend-of-the-club Paul Graham Raven had been making “notes toward the declaration of the Butlerian jihad” all the way back in 2022. Mea culpa, PGR! I’ll see you at the barricades.

Recommendations + Fellow Travelers

Last month I attended the Nebula Conference for the first time and had a great weekend meeting fellow SFF writers, talking shop, and generally making a nuisance of ourselves around Pasadena. A couple authors with interesting recent projects I want to highlight include:

Rachael Kuintzle is an author, scientist, and organizer who editor-in-chiefed this anthology of stories by researchers at CalTech and JPL, Inner Space and Outer Thoughts.

Alex Kingsley is a multi-talented creator with a collection of weird tales out and a novel about intelligent space crabs coming in October. Not to mention podcasts, games, plays, and etc.

Greg Leunig was one of several authors who mentioned solarpunk on various panels without any prompting from me! It truly is A Thing in the genre now. After one such panel Greg and I did a bit of a book swap. Check out his novels Colossus and most recently Cold Wind Blowing.

J. Vern Hoffman is a Pixar artist and also an author and also an all around delightful person. He’s got a trippy sounding science-fantasy epic he’s querying right now, so if you’re an agent or publisher, check out this excerpt.

Gwendolyn Maia Hicks attended the Clarion Workshop with me in ‘22, so it was great to catch up with them at the Nebulas (along with all the other Clarion Ghosts in attendance). They recently had two lovely publications, “The Heart That Beats Behind the Bones” in Hearth Stories and “How Islands are Named” in The Lit Nerds.

Though I could have spent less time with Rusty Bowers, a man who worked his whole life for the wrong side of progress and liberation only to be lauded as a hero for one moment of "are we the baddies?”

Appreciating this piece, thanks! To make clear for audience where the valley's utility power now comes from, it would be great to add a footnote on that. On "the foreseeable future is not about people abandoning cities like Phoenix en masse — it’s about more cities becoming more like Phoenix every year" - i think there may be some extent of 'both/and' - some will abandon and have abandoned hotter locations, more gradually than en masse, while more cities also work at adapting to accommodate residents where they are.

Equitable water management is a key factor; Tyson Yunkaporta in a recent June 'cast https://www.podchaser.com/podcasts/the-other-others-3674704/episodes/mongrelling-the-borders-214309483 mentioned at 36 min. an Australian govt foreclosing move:

"Queensland's putting laws in place where...nobody's allowed to collect water that falls from the sky.... there's places where there's water tank restrictions and stuff like that because...’no, it belongs to the government...we need every drop of it to fall...so that these assets are worth something that we're selling, and these water rates’."

The full episode is illuminating, also gets into Roma, Aboriginal and other traditional cultures' seasonal migrations. Livable futures, whether populations migrate or commit to a specific landscape, require community-driven governance to come up with sensible systems for essential resource access and distribution.

Great piece (and I loved 'Space is dead', which I read in the book version of Speculative Insights). In addition to all you've said here, perhaps it's also true that one of the reasons we're in this situation is the multiple centuries of trying to heat 'superior' northern places in order to make them liveable.