This week we heard the sad news that SFF author Terry Bisson had died at 81. I never met the man, but I’ve been a great admirer of his work. Bisson was a prolific writer and also a committed leftist. His stories could be jokey-funny (see “They’re Made Out of Meat”) and also profoundly moving. When I think of the writing life I’d like to aspire to, sometimes it looks a lot like Bisson’s.

I’ve been feeling a certain kinship with Bisson this past year because his third novel, Fire on the Mountain

(pub. 1988), is a utopian alternate history. I am hoping that my own third novel will also be a utopian alternate history. This is a project that’s been brewing in me for years, particularly this past year, when, thanks to a grant from the Arizona Arts Commission, I’ve been able to carve out time for research and development. In the process I’ve given myself a crash course in alternate history as a genre.

One of the best ways I’ve found to organize one’s thoughts about a huge swath of intellectual and creative space, is to write a syllabus. So I created a syllabus for a hypothetical “Alternate History 101” class, which uses alternate and counterfactual history to explore theories of how social change unfolds. The idea was to read AH novels/stories alongside social science texts, learning both about the genre of literature and about historiography and sociology, getting students to ask which parts of our contemporary condition were inevitable and which parts are contingent.

Here’s a quick rundown the units:

Unit 1: What If We’d Lost The War? - Starting with AH’s favorite tropes, alternate outcomes of WW2 and the US Civil War, reading PKD’s The Man in the High Castle and Ben Winter’s Underground Airlines.

Unit 2: Kings, Assassins, and Other Great Men of History - Exploring the “great man theory of history” first by reading the first instances of AH (pre-modern counterfactuals about Alexander the Great and Napoleon) and then by exploring a particular fixation of 20th century AH writers: the Kennedys.

Unit 3: Guns, Germs, and Steel—and Steam and Rockets? - A long unit on technology as a driver of history, reading Civilizations: A Novel by Laurent Binet and KSR’s The Years of Rice and Salt, then going into steampunk (The Difference Engine), and finishing with alternate histories of the space race (which I discussed a couple months ago). Along the way dipping into the debate over Jared Diamond, touching on Thomas Kuhn, etc.

Unit 4: If America Should Go Communist / It Can’t Happen Here - How close America might have gotten to very different political system? Reading “The West Is Red” by Greg Costikyan on the one hand and The Plot Against America by Philip Roth on the other——as well as, crucially, Bisson’s The Fire on the Mountain.

Unit 5: Sorcerers, Superheroes, Time Travelers - Where does AH end and sci-fi or fantasy begin? Considering the role history and social realism play in the broader landscape of SFF.

Unit 6: Alternate Futures - Concluding by turning the tools of counterfactual thinking to look forward instead of back, considering scenarios-based futures, including my own Our Shared Storm.

(If anyone would like to hire me to teach this class, please email!)

This syllabus is largely built around the way alternate history fiction gives us a chance to think about social science theories that we could never prove or test, but that nevertheless have a certain appeal. For instance, I read Civilizations——in which the Inca discover and conquer Europe——as suggesting a kind of ‘outsider’s advantage’ to first contact encounters. Binet’s alternate Atahualpa shows up on the 16th century scene unbeholden to Christianity or the vast web of relations that made up European aristocracy. This gave him a freedom that homegrown power-players lacked——in much the same way that conquistadors and other European génocidaires cared nothing for the customs and social structures of American Indigenous peoples.

Bisson’s Fire on the Mountain implies probably my favorite piece of alternate history hypothetical social science: the idea that our success as a species hinges on how many people we allow to live up to their potential and contribute meaningfully to our collective advancement.

The novel imagines that——for various circumstantial and strategic reasons——the 1859 John Brown- and Harriet Tubman-led slave uprising is a success. Revolt spreads across the south, and freed slaves secede to form the country of Nova Africa. This country embraces socialism, inspiring revolutions around the globe.

Most Civil War alternate histories feature a triumphant Confederacy, so the idea of going in the opposite direction, closer toward liberation and utopia, has stuck with me since I first read Fire 5-6 years ago. What makes Bisson’s book so provocative and powerful is that the historical revolt narrative is paired with a frame story set in 1959. In that part of the book we see electric cars, biotech shoes, and Black astronauts landing on Mars——a full decade before our paltry timeline merely reaches the moon! Partly this acceleration of human development is chalked up to socialism, but there’s another, deeper theory as well: the idea that our real world technological advancement has been hindered by the squandering of human potential.

In our timeline, slavery went on longer and was followed by racist regimes of Reconstruction, Jim Crow, segregation, and a white supremacy that continues to this day. Millions of Americans were (and still are) deliberately excluded from education and good jobs. Meanwhile colonial exploitation of much of the planet went on for an extra century, keeping hundreds of millions from participating in modernity. Two world wars and a global economic depression lost several decades to chaos and ruin.

What if those countless millions were allowed reach their highest potential, to contribute to their fullest capacity? What if millions more people had been given the chance to become great inventors, workers, theoreticians, artists, writers, leaders, thinkers of all types. Some of the global underclass did become great thinkers, of course, despite the forces that tried to keep them in their place, but this is just the exception that proves the rule. In this scenario of increased human flourishing, how far might we have come by now?

We are often told that war drives technological advancement, but war is just one excuse to mobilize resources into projects that aren’t limited by the market. Might we have achieved similar ends through programs that don’t destroy lives and blow up useful capital? Some years back I did a design fiction project imagining propaganda from an America that took climate collapse as seriously as it took the Nazis. Unfortunately, the Cold War split the world apart and stymied, perhaps permanently, our ability to have a rational conversation about global economics. Our laggard response to the climate crisis is a direct result of the structures that capitalism and empire have developed to maintain the status quo at the expense of unlocking planetary civilization’s full potential.

This last is a key idea behind my own work-in-progress utopian alternate history project, and it very much takes its cue from Bisson. I want to build on his thesis, bringing it into the context of our present day environmental polycrisis, and also expanding the franchise, asking who else has been excluded from our marshaling of knowledge, productive forces, and societal potential.

In small ways this idea is trickling out there. In the original Project Drawdown book, Paul Hawkins argued (with numbers to back him up) that education and rights for women and girls is a more powerful tool for stopping climate change than solar panels or wind turbines (on a dollar by dollar basis——we need the solar panels eventually). Maybe one day we’ll get to the point of being able to calculate precisely how mass human flourishing translates into knowledge and innovation. Or maybe that social science will only be possible in alternative timelines.

Anyhow, RIP to Terry Bisson. Thank you for the dream of emancipation stretching out through time in both directions.

Take My Clarion West Class in March!

Three Saturdays in March I’ll be teaching a course on solarpunk and climate fiction, part of the Clarion West online workshop series. The combination lecture and workshop will help participants craft stories to submit to venues like the Grist Imagine 2200 climate fiction contest. I’d love to have readers of this newsletter in the class!

Check out the details and register here!

News + Reviews + Miscellany

My Analog Magazine story “Family Business” (with Corey J. White) was reviewed and recommended by Mike Bickerdike in Tangent, and was included on Tangent’s yearly recommended reading list.

Similarly, Maria Haskins, a wonderful writers and reviewer of SFF short fiction, included two of my stories——“Any Percent” and “The Uncool Hunters”——on her 2023 Recommended Reading List.

2022 Best of Utopian Speculative Fiction by Android Press, which includes an excerpt from my climate book, is now out and available as an ebook!

Recommendations + Fellow Travellers

My good friend

just launched a fascinating new podcast, Experience.Computer, in which he interviews interesting people about how they perceive and interact with devices and digital spaces. I’ve honestly never heard a podcast like it. Really worth a listen+subscribe.After five years of finding its footing as an online leftist publication, Damage Magazine has released their first print issue, Building Big Things——a topic close to my heart! My copy arrived last week, and it looks great and reads even better. I’m friends or friendly with many of the folks involved in Damage, and I can’t recommend their perspective enough. If you’re into fresh, principled, big-thinking socialist thought, you should go ahead and subscribe.

Art Tour: The Sphere

Over the December break, we went to Vegas for a couple days to research C’s brilliant new novel project. Of course we had to see The Sphere, the city’s newest, most ridiculous, most massively unprofitable attraction. Inside is okay, a kind of low-rent Museum of the Future combined with a suped-up Omnimax theater. But the outside, it’s bizarre presence on the skyline…I’ve never seen anything like it. Frankly, as others have said, it whips.

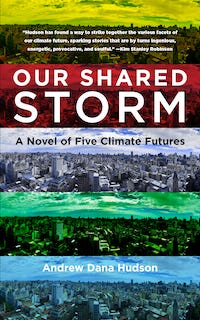

If you like the this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent climate fiction novel Our Shared Storm, which Publisher’s Weekly called “deeply affecting” and “a thoughtful, rigorous exploration of climate action.”

"the climate crisis is a direct result of the structures that capitalism and empire have developed" nailed it dude

Lmk when the course starts