In Which I Coin the Word “Omelian”

As happens periodically, “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas”——the classic short story by the G.O.A.T. Ursula K. LeGuin——has been having a moment. It was referenced in a recent Strange New Worlds Star Trek episode, and more importantly I’ve seen a bunch of posts and memes like the above and below roll through my feed. Obviously it’s an award winning and extremely memorable story, and in the SFF world many seem keen (for better or worse) to write their own twists on or responses to LeGuin’s story. Still I’m kind of surprised that Omelas has entered the online consciousness enough that we can crack viral jokes about it. Or maybe it’s the other way around: the jokes have made it yet more famous——like how Tumblr bits have taught millions the name of a specific Mesopotamian guy who, allegedly, sold some subpar copper almost 4,000 years ago.

Dark comedy aside, I think it’s interesting that “Omelas” has been peaking in our current collective vocabulary at the same time that an extended call for more hopeful, positive, utopian sci-fi is finally starting to bear out. Dystopia and apocalypse in fiction feel out of fashion compared to the heyday of The Road and Hunger Games that stretched from the mid-aughts to the mid-teens. Given the headlines and experiences of the last few years, perhaps these days pessimistic sci-fi can simply label itself as “realist.” But in truth we are seeing a flourishing of utopian thinking both in SFF and in lay futurist works that use fiction as an activist communication tool.

This summer at Clarion, I wrote a couple stories that had a utopian/post-capitalist bent. I was surprised at the skeptical interpretations some of these received via our ‘Milford Method’ of blind reactions. A few of my classmates seemed to assume that the worlds of these stories had a dark, dystopian underbelly hidden in the subtext. The streets seemed to them dismal and decaying, when in fact I had merely described them as rainy. A brief mention of what, to me, seemed like a better, post-carceral justice system to them implied an oppressive police state without rights to a fair trial.

Call this “Omelian thinking.” It is the (not unfounded!) sense that peace and prosperity are necessarily built on oppression, exclusion, exploitation, and/or genocide. In other words, it’s being on the lookout for the kid in the basement that makes the whole project of a supposedly better world morally bankrupt. There are two sides to this: the critical theory side and the narrative expectations side.

On the real-world side, there is a growing understanding that capitalism, white supremacy, and colonialism are 1) bad, 2) pervasive, 3) linked to the accelerating polycrisis. Most every country that styled itself one of the good guys in the struggles of the 20th century had a deep (and ongoing) history of carrying out atrocities against indigenous/Black/foreign/queer/working underclasses. Many of us are increasingly skeptical of stories of unalloyed progress, especially since we seem to be entering the environmental “finding out” stage of industrialization’s fossil fueled “fucking around."

Then there’s the demoralizing failure of a variety of utopian counter-hegemonic projects over the last century. Revolutions often turned bloody and authoritarian, seeing like a state missed critical aspects of human diversity, and both small communes and global communism collapsed due to internal contradictions and external pressures. These very real failures were then weaponized into propaganda by those with an interest in preserving the status quo, who would like us to fear any change to the present order no matter how sensible. I don’t think LeGuin, a brilliant critic of capitalism, was taking shots at revolutionary efforts (quite the opposite), but in this broader context it’s easy to see how conservatives and neoliberals might take up the banner of Omelas.

On the narrative side, we’ve learned, as readers and watchers and gamers, to be on the lookout for false utopias. If we are given a description of a society where everyone seems to be happy, we know that the author is probably going to knock that setup down by the end of the story——if only because modern stories are driven by plot twists, irony, and other expected subversions of appearances. Omelas is hardly the only example, though it is maybe the most pure, the best at reducing the archetype down to the simplest form of the thought experiment.

I recently played through Bioshock Infinite (2013) on the Switch, and the game takes great pleasure, during the first act, in slowly introducing notes of racism, worker exploitation, and religious mania to the architectural triumphalism of its flying, retrofuturistic wonderland setting. Actually, the whole thing is very Omelian, from the way the player first enters the city of Columbia on a festival day to the locked up young woman on whom the whole project depends.

In part the word “utopia” is misleading. It implies an impossible world without flaw, conflict, or unhappiness. By now everyone knows that word itself can be translated literally as “nowhere.” (I always remember the sendup of this gotcha in Dinotopia, a picture book about a utopian society where people coexist with dinosaurs, in which a cranky human character notes that in Greek “Dinotopia” means “terrible place.”) And since perfect social harmony does indeed seem incompatible with human freedom as we know it, there have been various attempts to rework the word into something more nuanced: eutopia, protopia, ecotopia, etc.

It’s a reasonable bet that we are never going to achieve a perfect society, and that living beings will be constantly moving from one set of conflicts and frictions to another for as long as they exist. In other words, politics continues, as I am always keen to argue.

But does that mean that we can’t imagine worlds/futures in which some of today’s major social challenges are solved/resolved/moved past? Futures that, while not perfect, are measurably happier, healthier, more equal, and more just than our present? If not utopia than just a “better-than-this-topia”? Or will we always be Omelionaires, our good times enjoyed only because of the degradation of others?

One key question of our current moment is: can technoprosperity be decoupled from exploitation, inequality, and environmental degradation? Bright greens and ecomodernists say yes, dark greens and degrowthers say no. Solarpunk, I think, often falls in the middle, with futures built somewhat on decoupling (renewable, clean energy) and somewhat on big cultural shifts that redefine “the good life” away from consumerism and towards community.

Personally, I think progress doesn’t have to be an Omelian bargain, but I also think decoupling will be hard, and imperfect, and by the time it’s achieved we may have passed through the hype cycle and take it for granted. (“Socialism” often just feels like good policy when put into practice.) And I think the project of building a better world is going to take a lot of imaginative thinking that only makes sense when approached in good faith. Good faith that falls apart if we always assume there’s a child in the basement.

So while I love LeGuin’s story, I’m a little wary of our modern Omelian skepticism. I’m hoping that by giving it a name, we might be better able to identify when we are engaged in Omelian thinking and whether or not it might be counterproductive. And I hope the term can help writers and creatives answering the clarion call for more optimistic SFF avoid triggering these utopia=secret dystopia reader assumptions.

It takes a very subtle touch to pull this off. One of the more successful works of our contemporary utopian moment, Becky Chambers’ A Psalm for the Wild-Built, uses a few different strategies to keep the Omelian instinct at bay. First, she gives us a protagonist with a lot of familiar negative emotions (anxiety, awkwardness, stir-craziness, obsession, etc.) through which to experience the world’s elegant, gentle, beautiful, and just social institutions. This is kind of the judo-reverse of a classic literary maneuver: the plucky and/or upbeat protagonist whose sugary charisma helps us swallow a story set in a pretty grimdark world (think Luke from Star Wars, Kelsier from Mistborn). Second, Chambers was clear that her harmonious world was achieved only after a tumultuous history filled with exploitation and environmental destruction. Third, the book often dwelled on the complexities at various scales that had to be navigated to keep the society functioning. All three of these are probably solid strategies for utopian fiction moving forward.

There is tension in speculative fiction between the deployment of allegory and metaphor to critique our present circumstances and the work of trying to articulate new ideas about how society might be organized and think new thoughts about how life might be lived. Writers get a lot of training in the former, but, even when pulled off less smoothly, I think the latter often ends up being more memorable.

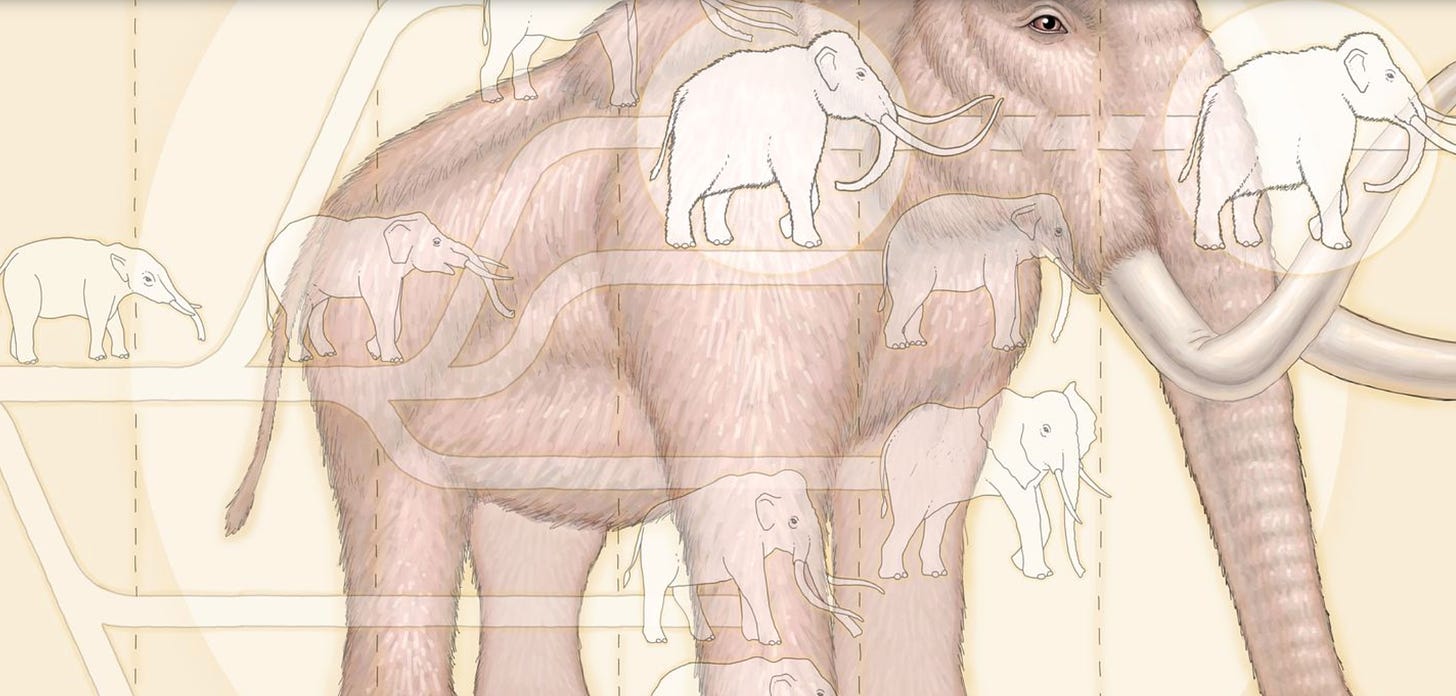

“The Mammoth Steps” on The Long Now

A favorite story of mine, about a de-extincted mammoth who goes on a foot trek across Asia with his teenage human bestie, has been reprinted by The Long Now Foundation as part of their Ideas series. (This story was originally published in Terraform and can be found in the recently released best-of anthology Terraform: Watch/Worlds/Burn.)

Publishing this piece with Long Now is a real treat, since it was through them that I first learned about the germ of the story: the Pleistocene Park project, an initiative to restore the mammoth steppe ecosystem in the arctic as a way to protect permafrost and fight climate change.

They were also kind enough to include an introduction I wrote about the story, “Talking to Terrestrials,” originally published when the piece was reprinted last year in Multispecies Cities: Solarpunk Urban Futures. I’m very proud of this essay, which lays out some of my thinking on how we should relate to animals, the futuristic multispecies civilization that might be possible if only we made it a priority.

Anyway, this little story I wrote on an overnight stay with C at Arcosanti has turned turned out to have quite a long life. So give it a read if you haven’t yet.

Upcoming Events

October 15th (2pm) I’m returning to Revolutionary Grounds in Tucson for a book reading and discussion of the upcoming COP27.

October 25th (15:00-16:30 CET) I’ll be speaking on an IPCC webinar titled “Communicating climate futures: Insights from communications professionals.” Link to come, which I’ll share to Twitter.

Press Clips, Reviews, Interviews, Etc.

The Climate Fiction Writers League newsletter published a really interesting email conversation between myself and Clean Air author Sarah Blake, about our recent novels, dystopian utopias, and "death of the cli-fi author" when events overtake books.

Compass, the magazine of the Association of Professional Futurists, included a kind, thoughtful review of Our Shared Storm in their September issue, written by Eben Kowler.

The American Energy Society publication Energy Today featured Our Shared Storm in their ‘Second Chance’ book list this week.

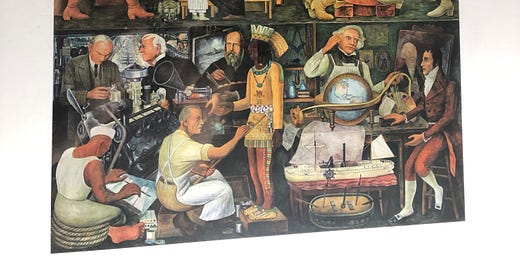

Art Collection: Pan American Unity

As mentioned last month, the Diego Rivera exhibit at SFMOMA is really excellent. Along with a print of Symbolic Landscape, I came home with the above print of the rightmost section of Diego’s huge masterpiece of a mural, Pan American Unity. It’s really a stupendous work, with so much detail and symbolism it’s hard to hold the whole thing in your mind at one time. I found this section particularly compelling and——with its checkered depiction of labor, science, technology, development, and art——a good fit for this month’s newsletter. Check out the whole thing.

Material Reality

Today was our first day of getting the back yard in order for the fall growing season. We put it on the calendar a few weeks ago, hoping things would have cooled off by now. Though we’ve had a properly rainy week, it’s nonetheless peaking over a hundred about half the time. So we confined our work to a couple frenetic morning hours, the four of us going out and assessing the situation and blitzing as much as we could before it hit 95F.

We swept the patio and bashed down the cobwebs. The end of the summer is spider season at our house, when we’ve been absent from the backyard long enough that black widows and garden spiders colonize the table, the clotheslines, the chairs and windows with cobwebs. We cleared out a bit of accumulation of junk, tidied up, and finished off with as much of a power wash as our hose jet can provide. Tonight we’ll go out and wipe a fresh layer of mineral oil onto the table.

The other big project was the compost and the garden plot. C laid down a layer of burlap over the weeds that have grown since we decided the lettuce had gone too bitter. Then we took our big city-provided compost barrel and tipped it out on top of that. I used a hoe to haul out the good, deep compost and spread it around, mixing in dirt from some of our dormant pots and garden bags. I spread everything around, tossed the still-decomposing scraps back into the barrel, and watered until it was soaked through. Then C but more burlap on top to preserve the moisture. Hopefully after a week or two of regular watering, we’ll have brought the soil back to life enough to start planting.

It’s quite incredible how much more four people can accomplish in 90 minutes than one or even two two people can manage in a whole morning or day. For the first time in years it seems like we might have a full house of gardeners. We’re talking about doing squash, rhubarb, tomatoes, herbs, along with our big lettuce bed. Maybe some Three Sisters setups. It’s exciting to be tackling this with our housemates, and not be entirely on our own.

One unexpected find: we have a single volunteer ear of corn tucked away in a corner where we used to keep our compost pile. My parents’ long running struggle to successfully grow corn has been a family joke for thirty years now, and so I’m excited to see if, by neglect, I might have somehow broken the curse.

My parents always grew corn and it was the garden highlight of the summer. One summer we went away for the entire summer. My father spread corncobs on the whole garden for it to remain fallow for the summer. However when we got home the entire garden was one big patch of field corn...with one exception: my brother had planted some sunflower seeds at the very end. Towering over the corn field was a row of sunflowers.