Final Exerpt: "If We Can Do This, We Can Do Asteroids"

what does a bodega look like under socialism?

Here’s the final excerpt I’ll be posting from my upcoming book Our Shared Storm: A Novel of Five Climate Futures (previous ones here, here, here, and here). The book illustrates a set of climate scenarios——the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs)——and the culture of the global climate negotiations (aka The COP) in each. SSP1 is the sustainability scenario, in which we successfully transition off fossil fuels, adapt justly to the climate changes already baked in, and build a more peaceful and equitable society. This section revisits each of our core characters——Noah, Luis, Saga, and Diya——to see what they are up to in this optimistic future. In the scene below, they gather after Saga’s art performance to discuss how the transition is remembered...

There was a small smattering of applause when people noticed Saga’s return. She made her rounds through the room, thanking the clumps of guests for coming. The gallery emptied. Eventually only one group remained, Noah Campbell and a few others Saga knew. They were discussing their interpretations of her performance, which Saga would prefer not to engage with. But Diya Kapoor was there, and she felt obliged to tell the famous climate leader goodnight.

“For me it evoked a very retro feeling,” Tara McVey, another American, was saying. “Like it was referencing all those expectations of apocalypse and collapse. There really was a fear, before the Transition Era, that everything would fall apart really quickly and violently. People had trouble imagining how smooth the transition could be, how much sense most changes would make when governments were stirred to act. I think a few of the shock-and-awe images were from old movies.”

“For me, I think it reminded me of the opposite,” Noah countered. “We have this sense now of, like, ‘of course things worked out this way.’ But really, they didn’t have to. We could have made worse choices, or lost a bunch of coin flips no one remembers anymore. And I think we have this gradualist narrative. That things were smooth, like you said. But that’s because we’ve already erased from our collective memory a lot of the worst of the ruptures. It took real struggle to finally get climate action. Direct action, strikes, even a little violence.”

“Well, of course,” Tara said. “But compared to the horrors of the 20th century, the climate movement was extremely nonviolent. There were sit-ins and occupations and general strikes, but no assassinations or bombings, at least not in the US. Just peaceful protests!”

“Yeah, but my parents were at all that stuff, and they always say there was no such thing as a nonviolent protest—just ones where the protestors didn’t fight back.” Noah shrugged. “Plus, nobody likes to talk about the pipelines that got sabotaged, or the threats and harassment that got coal plant operators to desert. But making carbon energy companies harder to operate was a big part of why investors eventually threw the old fossil giants under the bus, trying to buy themselves time. And reimagining politics produced a lot of hate and distrust. I remember growing up, we’d occasionally encounter sad, sick people who were camped out in the woods, sure the government was about to come euthanize them as part of some sinister population control program. Then when the population started to dip a lot faster than people had expected, there were even more conspiracy theories.”

“So that’s what you got from the piece?” Tara said, nonplussed. “That the Transition Era was messy?”

“What I got was a reminder not to feel so smug. We talk like it was all part of some inevitable enlightenment. But The Enlightenment was a culture war too, with its own share of violence. So, to me, that’s what the ‘lying to ourselves’ bit meant. And maybe a warning that we aren’t immune to rupture now. If we forget the past, that kind of anti-solidarity could come back again.”

“I don’t think anyone my age forgets the strife and tension before—and during—the Transition Era,” Diya Kapoor said. “Luis, you’re the youngest here. What is your view?”

“Madam Secretary,” said the young Argentine, hair in a prim bun. He seemed to be choosing his words carefully. “I’m no expert. But my impression is that history has been a long process of stepping back from the edge. Once, many wanted to use nuclear weapons, and they had to be talked down. The time before the Transition Era was another edge. So, I’m thinking about the people I organize with, who I know so well. And I ask, do they have it in them to walk up to the edge, whatever edge it may be? Yes, I think they do. I don’t think that goes away.”

“Well put,” Saga said, stepping a little closer to the group. A couple of them started.

“Since you were listening, can you tell us who got it right? About your intent?” Noah put in.

“That’s a terrible question to ask an artist,” Saga said. Then added, “but I will say none of the videos are from old movies.”

“Regardless,” Diya said, in a tone that made it clear she was ending the discussion. “Saga, my dear, that was wonderful.”

“Thank you, Madam Secretary.”

“Just one question,” Diya added. “Does the work have a title?”

“I don’t like titles,” Saga said. “But in the promotional materials the gallery has circulated, it’s called ‘Nuestra Tormenta Compartida.’”

Noah started to fumble with his translator, but she stopped him.

“It means, ‘Our Shared Storm.’”

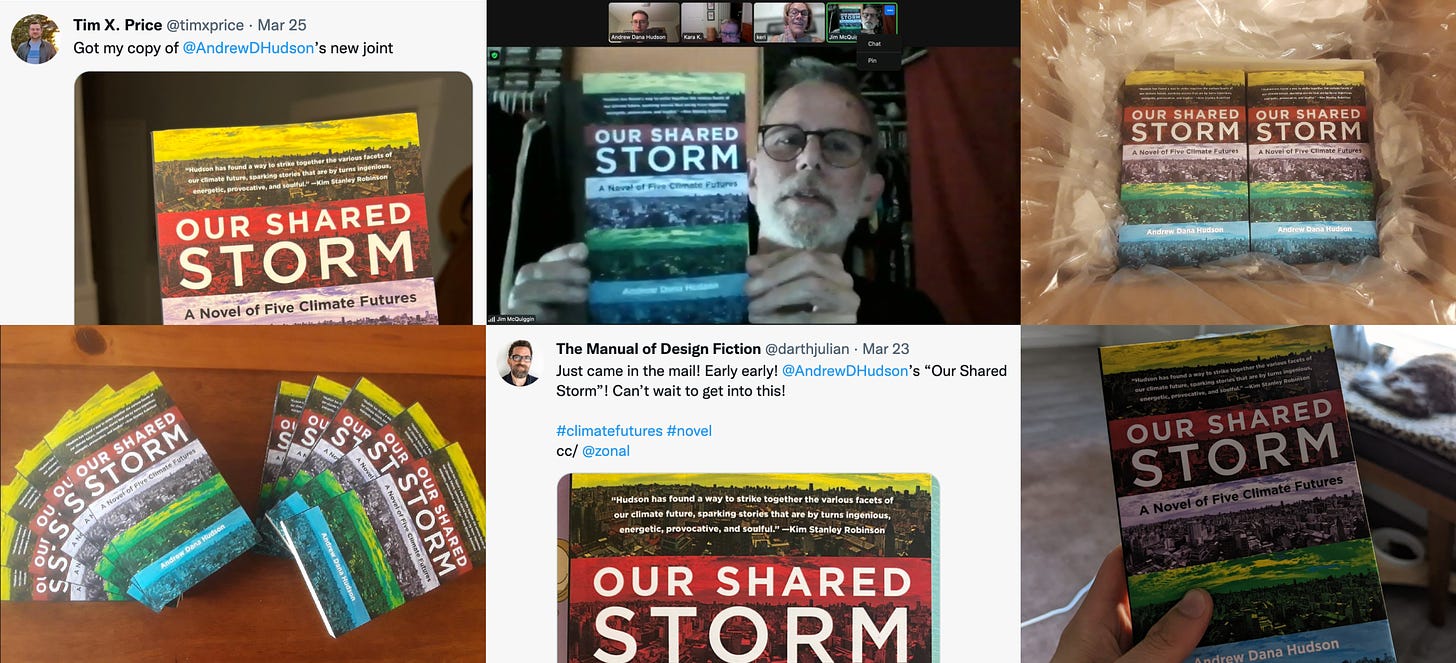

Our Shared Storm is out on Tuesday. If you order it from the publisher, you can get 30% off by using the coupon code STORM30. Here’s a handy button 👇

Happy Book Birth to Me!

Our Shared Storm is now officially in people’s hands——apparently paper pre-orders from the publisher arrived a bit early. As an object, the paperback looks great (my dad, who worked in publishing for years, approves). If you want to send me a picture of yours to add to the collage, I’d certainly enjoy receiving it! Can we get some ebook editions in here? I’m looking forward to getting my author copies of the pricey paperback version sometime this week.

And as a reminder, this book isn’t all wonky and serious. Here’s just a few elements that make it (I’ve been told) highly readable:

Places I’ll Be

Washington D.C., Thursday, April 28, 12pm EDT, ASU Center for Science, Policy, and Outcomes

Phoenix, Friday, April 29, 7pm AZ, Changing Hands PHX

St. Louis, Saturday, June 18, 2pm CDT, The Book House

Press Clips, Reviews, Podcasts, Etc.

Matt Holder published a review of my book in Strange Horizons. It’s mostly positive, taking some issue with the fact that I put “futurist” on my website——an arbitrary descriptor I seem to change up every month! Anyway, Holder admirably wrestles (as I often have!) with the limits of scenarios thinking and the trickiness of talking about climate change as a collective action problem, when in many ways a handful of billionaires and world leaders have all the power to fix it. I’m very gratified that the book has provoked such complex reflections, and I hope it will, as Holder suggests, be useful as a teaching tool for getting students up-to-speed on climate politics.

Andrew Liptak, of the Transfer Orbit newsletter, included Our Shared Storm in his list of April SF/F releases to check out.

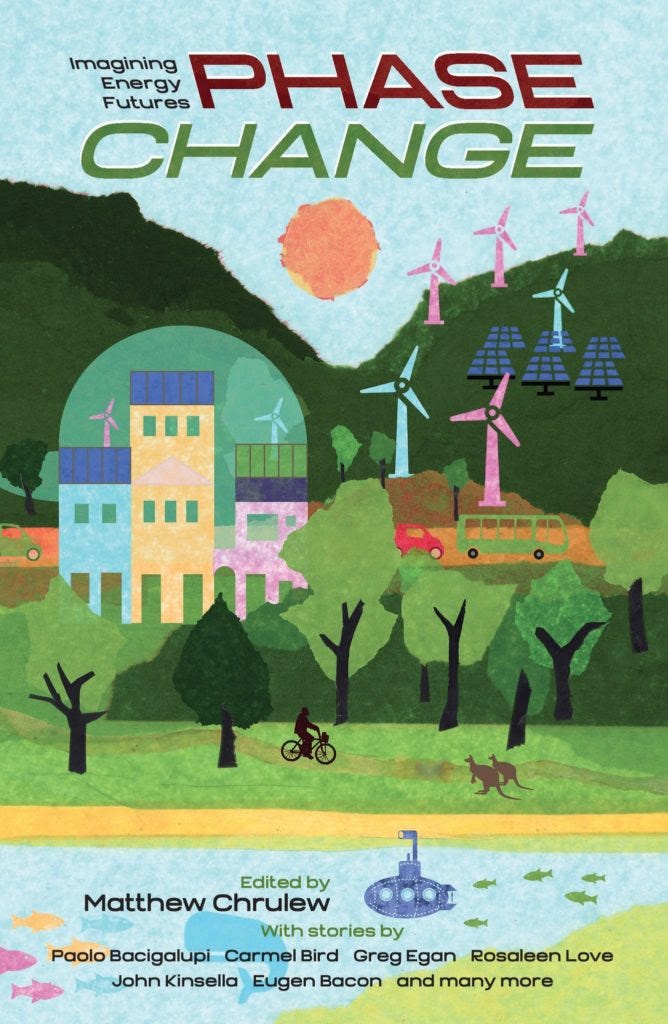

Cover Reveal: Phase Change

Very excited to have a story, co-written with Corey J. White, in this wonderful looking Australian volume on energy futures. It features a great cover and a truly stupendous TOC, including greats like Paolo Bacigalupi and Greg Egan, as well as authors I really admire, like Cat Sparks and Paul Graham Raven. I’ve mentioned “Boomtown” the story Corey and I did before, but it features rogue energy megaprojects, financial machinations, day-raves, and curing cancer. Pub date TBA.

Art Collection: Well-Stocked Shops

New acquisitions. One thing I’ve come to believe is that, so long as finances allow, if you see a piece of art you like and can purchase a print for ~$20, you should just buy it. It’s never a bad decision. Much like how, if you see the perfect gift for someone, even if you don’t usually buy that person gifts, you should jump at that opportunity. It’s a category of advice I think of often. I think I first read it over a decade ago on PutThisOn, but I think it holds true even after the peak of #Menswear-style wisdom.

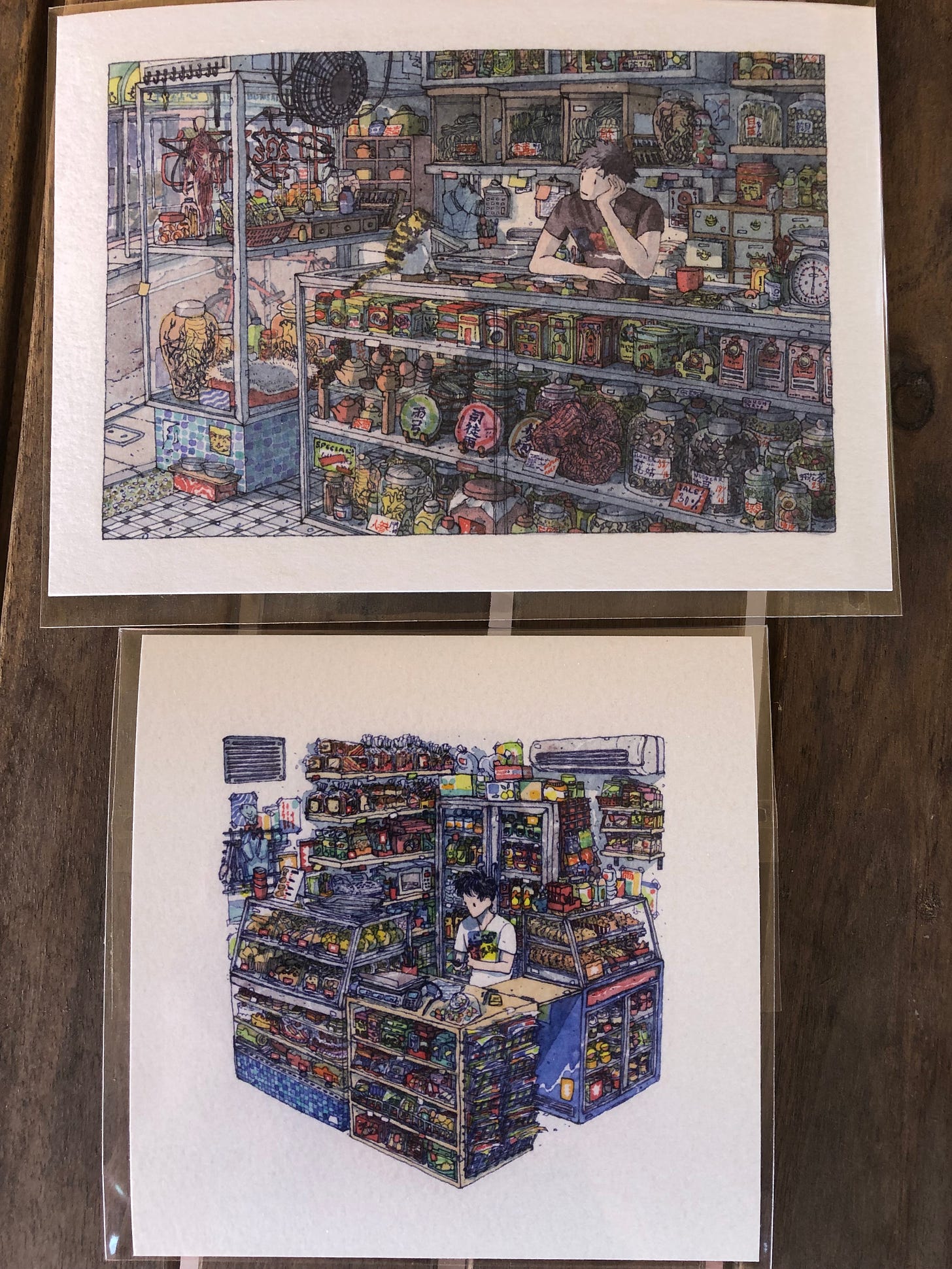

Anyway, the other day @TheJayMo sent me this post from the inimitable ThisIsColossal, and I just took to the pieces immediately. As everyone knows, there’s something very satisfying about cozy, dense, colorful spaces. It’s part of the appeal of a bunch of solarpunk art, particularly the paintings by Imperial Boy. These two (small!) pieces aren’t quite solarpunk, but they evoke the same vibe of wholesome, diverse, stable abundance that I think many of us in sprawling, precarious, big box America sometimes crave.

These in particular, from Rain Szeto’s Idle Moments exhibition, remind me of a question I often come back to: what does a bodega look like under socialism? I think we often have a vision of a planned economy operating on a massive industrial/agricultural scale. (I recommend Red Plenty as reading to complicate that picture.) But what does a publicly owned economy look like at the scale of the grocery or the corner store? Because I think we have good reasons to keep those sorts of institutions alive, rather than distribute everything out of big Walmart-sized warehouses or via Amazon-stye truck networks. Density and convenience are qualities people like in spaces and communities.

One answer is a kind of socialism that keeps money and markets, but gets rid of private ownership of the means of production. When firms succeed, the profit they make goes not to the investors that provided them with capital but to the state, which spends/distributes the money in a way that benefits everyone. This is the Matt Bruenig approach, which I think has a lot of merit. In this case the bodega is just a bodega, just subsidized by the government so long as the community wants to keep it around, thus ensuring that the bored shopkeep has a steady job that pays a comfortable wage, without much fear that a string of slow days might cost him his livelihood. If the bodega is popular and makes a bunch of money, perhaps prices will be adjusted down to make popular commodities cheaper or pricier items more accessible. The workers might get rewarded for their good work, their insights spread to other shops. But there’s no private owner behind the scenes hoping to use profits to buy more stores, to build a chain, to accumulate a planet-warping fortune like that of the Waltons——and willing to exploit his workers and customers to get there.

I also think we can imagine a kind of “decommodified bodega” that doesn’t quite use money, but rather is there to give out goods that are useful to have in the neighborhood: snacks, sure, but maybe also spices or niche foods/items that one occasionally one finds oneself in need of but not so direly as to warrant a whole trip to the grocery. Perhaps this shop/kiosk operates with a kind of librarian principle, steadily adding and trimming offerings and services, balancing popularity with a curatorial eye for social value. There’s a little bit of this in Becky Chambers’ Monk and Robot books. It’s the kind of project that sounds really fun and satisfying, that more of us could spend our lives on if we lived in a society where making rent and paying medical bills wasn’t an issue.

Most of Rain’s prints have sold out, but as I write this these two are still available for purchase here.

Material Reality

It seems like just the other day I was writing about the abundance of our lettuce patch. But now the weather has turned warm——I think we set a new record for the earliest day with temps over 90F——and the lettuce, while still abundant, is bolting and going bitter. We still go out and pick from it, particularly the redder varieties on the shadier side. But it no longer feels like every meal can or should come with a big pile of leafs. We’ve got some more bok choy that is coming up, but between the heat and the birds and the weeds we haven’t gotten around to pulling I don’t know quite if those will make it.

The problem really isn’t the plants, exactly. With the right shade and drip irrigation, you can grow plenty of things through the summer. The problem is pretty soon it’ll be too hot to enjoy working the garden——and our garden is not so productive that it’s worth working it if we don’t enjoy it. Just another small way that climate change can creep in and make our lives smaller, a little less. The good news is, we’ve learned a lot this season, and once the summer turns and things cool down again, we’ll get more lettuce going in the fall.