Sometimes you’ve got to be patient.

That’s a lesson, perhaps, of my new short story, “The Weather Out There,” published in Long Now Ideas, a publication of the Long Now Foundation, whose mission is to encourage long-term thinking. I’m a long-time Long Now member, from back when I was attending their in-person events in San Francisco most every month, and so it’s exciting to get to speak to their audience and contribute to their larger intellectual project. (Long Now also reprinted my story “The Mammoth Steps” back and interviewed me about my book in 02022.)

Patience is also possibly the lesson of the long journey this story had to finding a home. I first drafted this story seven(!!) years ago. That’s a long time to hold a candle for a story, but I really liked it, and so I never quite buried it in the trunk. In the years since it’s been through many revisions and rewrites, ballooning up to 10k words and back down to 3k. Eventually I pitched it to Long Now, and they took it right away. Of course an organization focused on long-term thinking would be the right place to publish this story about conversations that play out over centuries, messages traveling for decades through the murk of deep space.

This story is set is the Bay Area over a thousand years from now. For a good chunk of that future time, people have been in communication with an alien civilization, the Alsafi, some 19 light-years away. There is no ansible in this story, no faster-than-light travel, no way around the cosmic speed limit. If you had a question for the aliens, you’d have to wait about 40 years for an answer. It’s a slow conversation, but one that makes humans appreciate their environmental sustainability and organizational/cultural continuity. Until, one day, the Alsafi go silent.

The story follows Ferris, who works on the teams that send messages across the void, recording his thoughts in a journal that comes with his ancient Oakland house. As he tries to puzzle out what happened to the Alsafi, he rekindles a relationship with an old flame, Cassio, and, well, things get complicated.

Here’s an excerpt:

“Say there’s a lighthouse out there.” Cassio waved towards Marin. “It’s going to blink a message at you. What are all the things that have to go right for you to get that message?”

“You have to have line of sight,” I said. “And be looking in the right direction, at the right time. You have to be watching long enough to see the whole message, and you need a good enough memory to remember the pattern. Then you have to know how to decode it.”

“And,” Cass waved expansively, “it can’t be too foggy.”

“We’re pretty good at predicting the weather out there, you know.”

“I’ve never liked that metaphor. Tracking matter a dozen light-years away is nothing like watching for clouds on the horizon. It’s dark, and your model has to look decades ahead based on the thinnest flickers of shadow. Did you know they keep changing the estimates of how much dark matter there is in the universe?”

I did, but something about being there with her, on that beach, stirred a thought I hadn’t had before.

“In the histories the Alsafi used to wonder a lot why they never heard from anyone besides us,” I said. “They’ve always been more bullish about the chances of life in the universe.”

“You think if they got a transmission from someone else, they’d stop talking to us?” Cassio asked.

“A second contact changes everything about The Conversation. Do they tell us about them, or them about us? Whose permission do they need first? Who do they prioritize? It gets complicated.”

“Kind of like us,” Cass said.

She spoke low, barely louder than the surf. We let it hang there for a moment, the chimes of distant drift-ships rolling in and out of the Golden Gate.

“Kind of like us,” I agreed.

Long Now published this alongside reprinting an essay from this very newsletter, “Space is Dead. Why Do We Keep Writing About It?” (We slightly expanded and adjusted this piece, so check out the updated version on the Long Now site.)

This essay proposes that the huge amount of sci-fi written about spaceships, colonies on faraway planets, galactic empires, and daring astronauts might be out of sync with the sluggish or nonexistent progress we’ve made over the last 50 years toward such a spacefaring future. It finishes with a coda that we want to find out what’s out there in the universe and talk to aliens, we first need to figure out how to survive here on Earth. Perhaps we need to extend human life not out into space, but into time.

This is really the core idea behind “The Weather Out There” too. Its vision of futurity is subversively not that futuristic. It’s a thousand years in the future, and yet no one is uploaded into the singularity. There are no androids, or cyborgs, or genemods — at least not that show up in the story. They have various “equipment” floating in the outer solar system, but no mention is made of space colonies or humans traveling to or living on other planets.

Instead, some institutions seem different: money is not mentioned, and housing isn’t privately owned, and a different calendar is in use with different holidays. But places like Oakland and Berkeley bear the same names they have today (though no one mentions “America” or other nation states). It’s a future in which life is, for the most part, familiar. People are still living in houses and gardening in back yards, still commuting on public transit or by bike, still taking moody walks on the chilly beach.

My goal was to point toward a future that had stabilized. That was modern and sophisticated, but was no longer roiling with technological and social upheaval. I think we have a hard time envisioning such a possibility. We tend to think that, by the time we get to the “far” future, we’ll have either blown ourselves back to the stone age (or some other pre-modern state) or our technology will have rendered human life totally unrecognizable.

Is that what we want, though? Singularity and apocalypse certainly have their constituencies, but I’m doubtful of their broad appeal. What does a majoritarian future look like?

Well, if I had to guess, I think most people are grateful to be living with modern medicine and many modern conveniences, but are also somewhat skeptical of technology. (The college freshman I teach are very anti-tech this year.) Most people want their kids to benefit from progress, but don’t want them to entirely depart from family traditions. Most people don’t want to be beholden to the past, but also don’t want to be forgotten, buried by the rubble of history.

This is not a particularly sophisticated ideology, but I don’t think it’s unreasonable — though it’s got edge cases that get tricky, spots where the project of emancipation is deeply lagging and such a moderating impulse turns reactionary and hateful. Let (cis-hetero)patriarchy fall, and white supremacy be washed away, and animals be liberated, and capitalism be surpassed. And of course big changes must be wrought to the world to survive and roll back climate disaster. There are just upheavals that we should embrace and demand.

But on the other side of those, what are we going to do for the thousands of years yet to come? What if it never becomes practical or comfortable to spread throughout the stars, or transfer our consciousness into computer code, or time travel, or all the other magic sci-fi likes to imagine? What if we are just here, on Earth, with each other?

Must empires always be rising and falling, or might we achieve some kind of equilibrium? A rough shape of the world that can be preserved and maintained and passed down generation to generation without much objection. Institutions of continuity that keep the past from turning into a foreign country and allow the future to feel tangible and accessible.

Would we want that? Or would it be stifling? Would we find satisfaction in cathedral-time projects, or interstellar conversations? Or does life in modernity require a certain amount of churn to be meaningful? I don’t have answers, but I think these are good questions.

Maybe I’m thinking about all this because, this week anyway, the near future feels impossibly hard to imagine. The election holds us in a state of quivering quantum uncertainty, and either outcome could come with near-term violence by reactionaries and fascists. I realized today that Trump has been a constant presence and topic of conversation for more than a quarter of my life. For my students, it’s half their lives; they’re voting now, and Trump has been running for president since they were nine. As a person and a movement, he’s deeply, deeply oppressive to the imagination. He saps our attention and curdles our discourse and makes every discussion about the future begin and end with "Trump or not Trump.” Here’s hoping he loses, and we can finally start having a real conversation.

Read “The Weather Out There” in Long Now Ideas, and let me know what you think.

News + Reviews + Miscellany

Martin Hähnel had a nice comment on the aforementioned “Space is Dead” essay: “We can still dream of space. But we ought to do it not turning away from what we need to go through - system change - before we go beyond.”

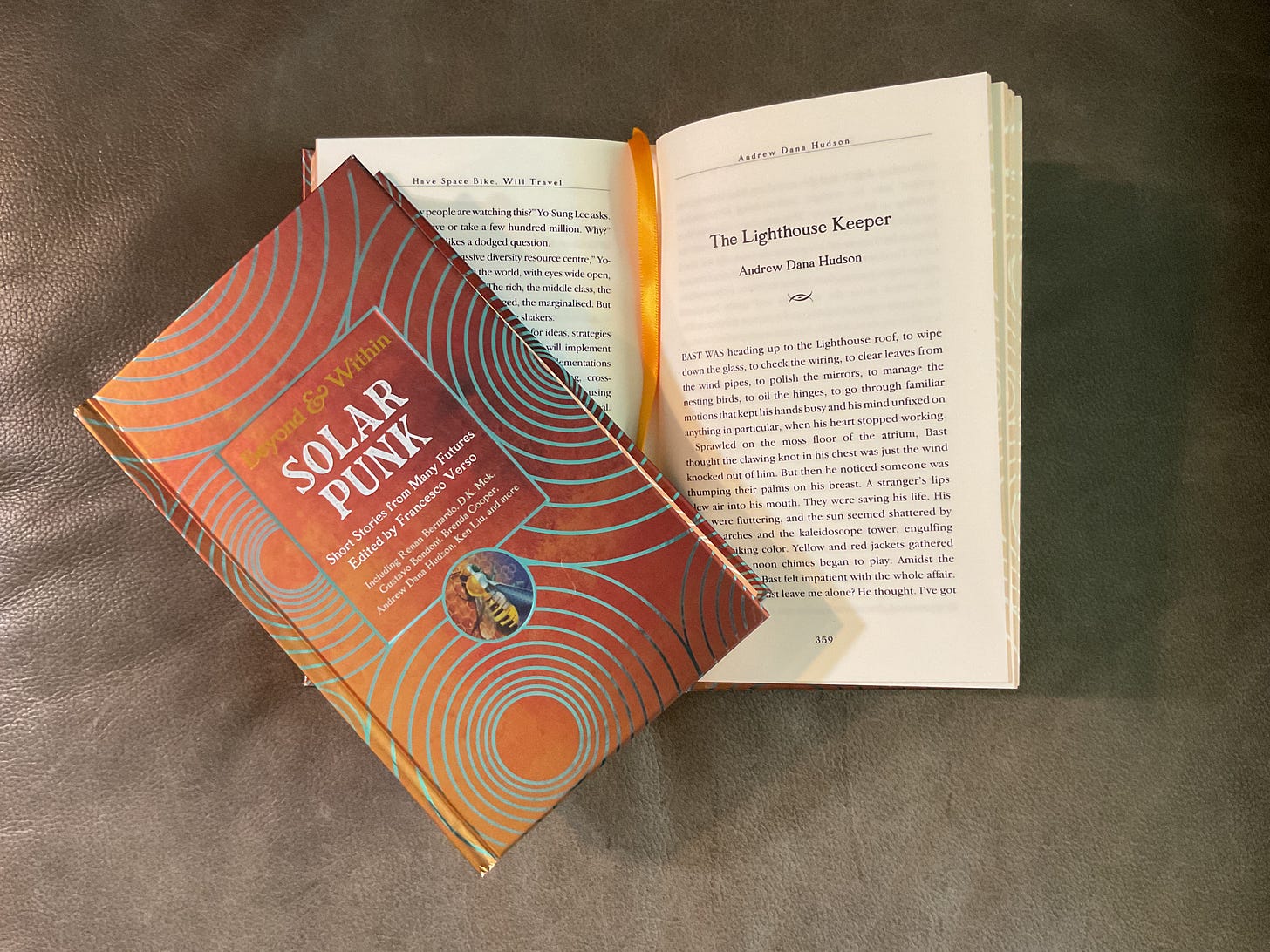

Solarpunk: Short Stories from Many Futures, edited by the great Francesco Verso and published by Flame Tree Press as part of their Beyond & Within series, is now out! It includes fiction by me, as well as Ken Liu, Sarena Ulabarri, Renan Bernando, and others. It’s a beautiful-looking and -reading volume, so get your copy here.

Recommendations + Fellow Travelers

Damage Magazine released their third issue, “Mothers,” featuring writing from a bunch of interesting people I know and like. Check it out!

D.A. Xiaolin Spires has a fresh story out in the latest issue of Clarkesworld titled “Luminous Glass, Vibrant Seeds.” I had the pleasure of workshopping this story with her last spring during my Clarion West class on how to write solarpunk and climate fiction, so it’s awesome to see it find a home in such a great venue. (She’s also got an essay in this issue about zero-g fight scenes.)

CY Ballard’s Cosmic Mystery Club dug into the unreliable explainer character in this essay on The Empty Man. You should subscribe!

M. M. Olivas’ novel Sundown in San Ojuela comes out in a couple weeks. Give it a preorder!

Art Tour: The Active Voice

Still thinking about this sublime rock I saw at the St. Louis Art Museum a few months ago.

If you liked this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my climate fiction novel Our Shared Storm, which Publisher’s Weekly called “deeply affecting” and “a thoughtful, rigorous exploration of climate action.”

Beautiful point - it stands to reason that there will be a moment when technology will finally fade into the background, reducing perceived scarcity, leaving humans to do human things because they want to - as social animals engaged in the good life.