There’s a saying that “a good science-fiction story should be able to predict not the automobile but the traffic jam.”

That’s how Frederik Pohl put it in 1968, though by then it was already hackneyed. I believe the phrase dates back to Isaac Asimov in 1953, who remarked in an essay that it was harder to predict the traffic jam than the automobile. Interestingly, he used it in the context of describing three types of sci-fi story: the gadget story (that culminates in an invention, like the car), the adventure story (a dashing hero uses the invention in high-octane action scenes), and the social SF story (exploring the ramifications of an invention on society).

In recent decades, I think the invention story and the adventure story have diminished in prominence, at least on award lists and in the most distinguished magazines. There’s still plenty of them around in one form or another — sad puppy fashfic and military SF and the whatnot — but today the social SF story is the dominant form of technology-minded futuristic SF.

Not that predicting the traffic jam will make people think twice about inventing or driving cars. Lately I’ve been seeing sci-fi writers have a real come-to-Jesus-moment about how much SF concepts like the metaverse or AI have been taken up as meaningful near-term goals by various evil tech billionaires and the noxious cloud of fans and wannabes that follow them around. (See Charlie Stross’s We're sorry we created the Torment Nexus.)

This has been brewing for a while, but is recently coming to a head. Partly we probably needed the useful ‘Torment Nexus’ meme to see it and discuss it clearly, but I think it’s due to AI. I’ve weighed in on this before, but since then I think a frustrated consensus has been forming among SF writers that it’s best to forcefully distinguish AI-the-sci-fi-concept (largely used as metaphor) and LLM chatbots. Ted Chiang was in town earlier this month, and he took great pains to argue that those who use sci-fi eschatological language to talk about these products are either dupes or selling dupes a bill of goods. Then just the other day I saw Cory Doctorow give a talk in Phoenix on enshittification, and he put-uponly joked to a questioner that the first person who brought up AI had to buy everyone a round of drinks.

Anyway, I’ve been thinking about Asimov’s traffic jams lately because it seems like the social science fiction story is evolving. Increasingly, it seems like science fiction writers are being asked to imagine not just the car and the traffic jam, but also the traffic light — as well as speed bumps, car pools, HOV lanes, congestion pricing, department of transportation planning commission meetings, and more. And maybe even bike lanes and busses and trains. In other words, not just predicting problems but also imagining solutions and even envisioning alternatives.

There are just a lot of calls out there for stories and narratives that have something useful to say about our current polycrises. The Grist cli-fi contest that Tory Stephens and I discussed in my last newsletter is a good example, but really there are a ton, from a lot of different sectors (academia especially), asking not just for fiction but for solutions-oriented speculative thinking in various forms. To some extent, the “call for better/greener/juster futures” is as prevalent a form of Solarpunk writing as the stories they solicit.

I think this evolution is being driven by three factors:

Science fiction is increasingly mainstream, and multiple generations have now grown up exposed to speculative thinking. Sci-fi writers have, for various reasons, become our de facto experts on the future.

We know about the Torment Nexus problem. People are realizing how much sci-fi ideas are shaping hugely impactful industries. There is a growing sense that we need to engage with the same medium if we are going to rethink a high tech future along less plutocratic lines.

The climate crisis has made the future a topic of concern for all of us, not just those interested in science and technology (or returns on their investments).

Now, when I say “imagining the stoplight and the train,” I don’t just mean we should only write utopian stories or stories about smoothly deployed solutions to all our problems. In fact, it seems to me just as crucial as ever to continue to anticipate hiccups and complications, to imagine how things might go wrong, to think in terms of the winners and losers under this or that future. One thing I’ve learned from talking to folks like Madeline Ashby is that people often hire futurists to tell them things they don’t want to hear.

When doing so, however, I think it’s important that we frame these potential traffic jams not as inevitabilities to either fear or ignore, but as points in a wide possibility space, and moments in time that can be followed by new solutions with their own complexities. Similar to the scenarios-based fiction I’m obviously fond of, the emphasis needs to be on the choices we can and will make and how best we can anticipate and live with the consequences.

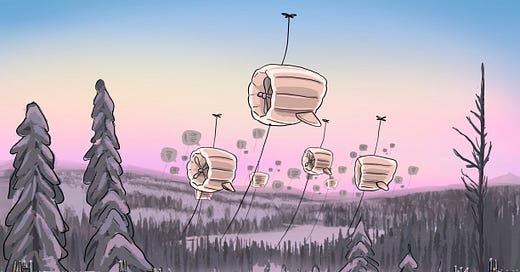

Anyway, all this has been on my mind because the four stories I wrote while in Sweden last year are finally online! The full book, which will include nonfiction companion pieces, is still coming, but you can read them (and see the lovely illustrations by Daniel Bjerneholt) on the Luleå University of Technology (LTU) website here.

Here’s a quick breakdown:

“Windy City” is set in a bustling and prosperous far north metropolis, where wooden skyscrapers look out on giant wind turbines that are also significant tourist attractions. The story is a summertime caper about two moms trying to game a highly financialized energy system — and getting caught up with a rowdy separatist movement as a result!

“The Wild Tour” has the north returning to its traditional role as a landscape of extraction to benefit Stockholm and the rest of southern Sweden — while also returning land to the long-marginalized indigenous Sami people. Fall-winter is setting in, and a bloody animal encounter beneath cable-tethered turbine balloons leaves a loner in the debt of some itinerate turbine workers who want to see the real, post-rewilding north.

“The Stillout” features a small, wind-powered village trying to maintain its energy reserves through an extended windless calm in deep winter. It’s a story of community tensions, resilience, and solidarity during a different kind of ‘climate event.’

“Spring Fires Day” explores a beautiful, greenhouse-covered city celebrating the coming of spring with the traditional moving of solar panels back onto roofs. However, political and familial tensions complicate this community ritual, as future generations start to have their own ideas about the environment and the energy transition.

These stories grew out of a series of “narrative hack-a-thons” about the future of the energy transition in northern Sweden. Northern cities like Luleå and Skellefteå have been embracing green industry and anticipating significant energy system and social changes as a result. People there are thoughtfully considering how to navigate those changes, including the influx of people they may bring. It’s a chance to reimagine what communities in the north look like and what the region’s relationship should be to the rest of Sweden.

These narrative hack-a-thons brought together scholars from a variety of disciplines, utility and municipal policymakers, students, and me. The explicit goal was to brainstorm possible future scenarios for the energy system and science fiction stories that could illuminate and complicate those scenarios. Many thanks to our partners and funders from the Arctic Center for Energy, Research Institutes of Sweden, Vinnova (the Swedish innovation agency), and of course LTU.

This is a methodology we largely based on similar projects I worked with the ASU Center for Science and the Imagination, which used such narrative hack-a-thons to produce the excellent solar futures books The Weight of Light and Cities of Light. Just this past month I had the great pleasure to participate in another CSI narrative hack-a-thon, this one on the immensely complex issue of consent-based nuclear waste siting. Looking forward to writing that story and having that book come out later this year!

The dimensions we used to guide our scenarios were the same ones used for the Weight of Light project: size of energy system units (big or small) and setting (urban or rural). However, our Sweden project did work slightly differently. Instead of having one workshop with four teams (each with a sci-fi writer that would write their own story), we had four workshops, each one with a unique set of participants. The only constants were myself and my LTU colleague/project mastermind Anna Krook-Riekkola, a brilliant energy systems modeler who made this whole thing happen.

We hoped that by having a single author (me) as a tentpole, we could make the stories more connected and comparative than the ones in the CSI books, which, while all pretty brilliant, don’t feel that much like diverging scenarios. We were shooting for a middle ground between those books and the highly comparative and connected scenarios stories in my book Our Shared Storm: A Novel of Five Climate Futures.

I think we somewhat succeeded in this, though we are still triangulating the perfect sweet spot. While the workshops were very generative, spreading them out over time and changing up the participants made it hard to do something as ambitious as create shared characters across the scenarios, the way I did in Storm. And the ideas that came out of the workshops had their own momentum that didn’t always fit nicely into a comparative framework. Also, for my own part, I found it hard to redo what I had done in my book, and instead looked for new creative and intellectual hooks to focus my attention on.

These four stories are all, to some extent, “predicting the traffic jam” stories. They look at the onrushing energy transition and imagine some possible complications in how we might feel once it’s through. There’s a certain melancholy to them. This was partly how I was feeling last year, coming out of the pandemic, moving across the planet to a new country, which wasn’t easy. It was also partly, I think, something I picked up on in Swedish culture and politics. I mean, check out this wild report from Kairos Futures, a consulting and research company I had the pleasure to visit with while in Stockholm: “Swedes, Daily Life, and the Darkness of Meaninglessness.” Oof!

Despite this, I personally think these stories are quite optimistic. In all of them, the energy transition is successfully accomplished, an enormous achievement. Their point is not that the energy transition is bad or should be avoided, a car that we would be better off never inventing. Their point is that we should remember that no transition is the end of history, that there will be new debates to argue over, always, in the decades and centuries to come, and that future generations will make up their own minds about the world they inherit.

We invent the car, we get the traffic jam. We invent the stoplight, and people fume while waiting for it to change. We add bike lanes, but maybe that’s not enough. We switch back to trains, and people miss the freedom of the open road. We invent self-driving cars, and people set them on fire. Around and around we go.

Anyway, please read the stories! I’m very proud of them and the great work my Swedish colleagues have done with this project. Looking forward to hearing what you all think.

Take my Clarion West class this month!

Starting March 16 and continuing for two Saturdays after, I’ll be teaching a course on solarpunk and climate fiction, part of the Clarion West online workshop series. The combination lecture and workshop will help participants craft stories to submit to venues like the Grist Imagine 2200 climate fiction contest. I’d love to have readers of this newsletter in the class!

Check out the details and register here!

Updates + Clips + Miscellany

C2 Montréal: I’ll be speaking at this very cool three-day conference on May 22! It’s an exciting multidisciplinary, multitopic event, and I’m stoked to get to be in conversation with artist Olalekan Jeyifous on the future of solar energy.

Agenda for a Progressive Political Economy of Carbon Removal: The report I worked on with the (newly renamed) American University Institute for Responsible Carbon Removal is now out! The report includes a series of short scenarios I wrote about the ups and downs, twists and turns the multigenerational CDR project might face. Check it out!

Alexandra Pierce at Locus had nice things to say about the excerpt from my climate book that appears in Android Press’s 2022 Best of Utopian Speculative Fiction. The excerpt “If We Can Do This, We Can Stop Asteroids,” is the last section of my book and also the last story in this collection. Pierce says, “It’s a story that challenges the reader: ‘Here, take these approaches and dreams and see if they might work now.’”

Another lovely review, by the Green Technology Education Centre Canada, this one of my whole book. A really nice part of publishing a novel is watching people you’ve never met encounter it for years to come.

Recommendations + Fellow Travelers

Shout out to newsletter mutual and extremely nice occasional correspondent Duncan Geere, who gave Our Shared Storm a shout out in his newsletter, Hello From Duncan. Duncan’s newsletters seek to “round up recent creative input and output,” which I think is a super compelling and productive format. Reading his newsletter, I always discover new things that don’t come across in my decaying social feeds.

Same goes for Johannes Kleske, who also shouted out my book in his newsletter The Futures Lens. I’ve been enjoying his efficient, insightful posts on critical futures studies and similar topics, and if you like reading Solarshades I bet you would too.

My friend and Clarion classmate T.K. Rex has a great story in Haven Speculative, “The Hen and the Shadow of the Monstrance Commune.” I really like this one, blending weird vibes with a thoughtful eye for social complexity and science, undergirded by the shades of an approach she calls “speculative memoir.”

If you like the this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent climate fiction novel Our Shared Storm, which Publisher’s Weekly called “deeply affecting” and “a thoughtful, rigorous exploration of climate action.”

ok I know this wasn't really the point of your essay. but im beginning to realize it's my duty to tell people this: the AI thing is not fake and overblown. it is in fact only going to get smarter and more central to our lives so it would be nice if science fiction authors would take it more seriously. actually.

what we have now is a bunch of people looking at the automobile and not even bothering to try to predict the traffic jam. but being like "it's simply a faster horse"