A strange part of writing about the near future is that occasionally I get to see life imitate my art.

Way back in 2018 I wrote a story titled “The Chaperone” about the business side of a tech giant that sold flirty AI voice assistants. The story followed Jan, a climate refugee and precarious Alpha employee, whose job it was to monitor and intervene when dudes started falling in love with the custom Siri Johansson voice in their computer. As Jan moved up the corporate ladder, she found out just how much the company actually wanted customers to anthropomorphize their AI products, because doing so created bonds of trust and dependence that could be manipulated for profit.

(You can read “The Chaperone” here thanks to the Wayback Machine, or pick up the Working Futures anthology it was originally printed in. And you can read some of my previous commentary on AI here and here.)

The story was very much a response to the movie Her (2013), so it was a bit surreal to see OpenAI’s recent ScarJo-like ChatGPT voice demo and read about the subsequent controversy. This has been much discussed, so, in short: the “Sky” voice they’d given the bot was eerily similar to the obsequious persona Scarlett Johansson used when voicing “Samantha” in Her. The notoriously litigious Johansson noticed and gave a public statement revealing that OpenAI’s shitty CEO Sam Altman had twice begged to license her voice, including just days before the recent demo. Altman is apparently still out there claiming the “Sky” voice (which they took down) was not intended to sound like Johansson — ridiculous given that he literally tweeted the solitary word “her” on the day of the demo. The whole thing was corporate farce on a grand scale.

Her is also apparently Altman’s favorite movie, which has driven home to me, and many others, just how extremely literal the Torment Nexus phenomenon turns out to be. What’s going on here?

There’s an argument to be made that science fiction has simply been very good at predicting the kinds of problematic technologies that would nonetheless be attractive to profit-seeking corporations and powerful plutocrats. Without sci-fi, would we simply be blindsided by various torment nexii? Would we moan that “if only someone had anticipated this torment nexus and warned us not to build it”?

Has sci-fi armed us to approach new technology with a critical eye, thus improving the speed and outcomes of our amistic decision-making cycles? Or has sci-fi actually sped up the creation of torment nexii by imagining them early, thus giving the rather dull and uncreative people that tend to run big technology companies a product blueprint they can try to make reality? Can we counteract the torment nexus effect by flooding the zone with narratives and images of more sustainable and humane technologies and futures (a la solarpunk)?

Attending the C2MTL conference in Montreal this past month, where in addition to speaking about solar futures I watched a few panel discussions on AI, it struck me that there’s a certain asymmetry going on in the debates around this stuff.

On one side you have very smart people arguing thoughtfully for a nuanced and critical approach to understanding these emerging technologies. They weave in philosophy, anthropology, sociology, history, and the humanities into helping us craft better, more useful metaphors and legislation that can balance downsides with opportunities. They help us see that when we talk to a chatbot, we are really writing a piece of fiction in which you and the chatbot are both characters.

On the other side, you’ve got guys who want to make “AI from the movies” real.

Now, I’m all for the nuanced examination of these new technologies, but there comes a time when saying “well, it’s a little more complicated” actually gets in the way of meaningful, clear discourse. In my perfect world, we’d use democratic deliberation to decide how to incorporate AI into our lives and economies, and how not to. That debate would hear out a range of opinions, and then we’d vote and abide by the results.

Right now the spectrum of sensible opinions one might hear at a venue like C2 ranges from people who want to go fast to people who want to slow down. The compromise between those two positions is “go kinda fast,” which I think is what we’re doing. There is no position meaningfully included in the debate that says “AI is simply bad and we should decide not to do it.” In response to such a position, one quickly hears that “the genie is out of the bottle” and there’s nothing left to do but try to make the right wishes.

Lots of people feel this way, though, I think. Last weekend I was at a sound bath cacao ceremony, which included a sharing session. Despite the fact that it seemed to me weirdly out of place in the yoga studio we were sitting in, several participants expressed anxieties about AI and the impact it would have on jobs and the economy. There were very much median American voters, trying to come to terms with a shift they objected to but felt they had no power to stop. Trust me when it tell you: “don’t do it” has a constituency.

Mostly AI’s detractors have taken to heckling, jeering, and loudly rooting for AI companies and products to fail. This movement has produced great content (see the various viral posts of Google’s AI-generated summaries telling people to eat rocks and glue), but not yet a clear demand or coherent ideology. It suffers a bit from what I call “we just hate these motherfuckers”-syndrome: a generalized anger at the rich and powerful, particularly the big tech companies that broke all their “don’t be evil” promises and have spent the last ten years enshittifying the digital lifestyle they got us all hooked on.

If we’re going to have a meaningful debate about AI that results in good policy and good products, I think we need to break that asymmetry. I think it’s time to fight sci-fi fire with sci-fi fire. I think we need the Butlerian Jihad.

What’s the Butlerian Jihad? The glossary of my copy of the classic science fiction novel Dune, by Frank Herbert, includes the following:

JIHAD, BUTLERIAN: (see also Great Revolt) — the crusade against computers, thinking machines, and conscious robots began in 201 B.G. and concluded in 108 B.G. Its chief commandment remains in the O.C. Bible as “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind.”

In the deep lore behind the Dune universe (and in a prequel written by Herbert’s son), humans collectively decided to abandon and prohibit AI and even computation more broadly. Instead they rely on spiced-up human minds to do complex calculations. In a way, this is another vision of “AI from the movies”: one in which we learn to be high tech and deeply futuristic without going down the path predicted by so many e/acc singularitarians.

I’m not the first to latch onto Herbert’s concept. For one, you can already buy the t-shirt. For two, Erik Hoel wrote a very similarly titled Substack post way back in 2021. Hoel was worried about so-called “strong AI” and the existential risks some people think would come with it. I’m not concerned with that here (arriving at our present era of LLMs has increased my suspicion that this AI takeover fear is just another science fiction story). But I do think the Butlerian principle of not making “a machine in the likeness of a human mind” is an interesting one to apply to our current moment.

What was so gross about the Alpha Assistants in my “Chaperone” story and about OpenAI’s ScarJo-esque “Sky” was not that these were conscious beings about to escape containment. It was that they were likenesses, cloying simulacra that present a bundle of system services and make us pretend that it’s a person. In the case of OpenAI’s demo, it was even a knock-off likeness of a specific real person, made expressly without her consent! Most of the noxious uses of genAI fall under this ‘likeness’ category: deep fakes, robot scam calls, social media bots, plagiarism, etc.

Meanwhile the energy demands of even the more benign uses of AI are turning out to be a real drag on the energy transition and our hopes for a stable climate. The US is literally pushing back plans to shut down planet-killing coal plants in order to meet the needs of the new massive data centers being built to amuse the “AI from the movies” crowd. If we were further through the energy transition, with surplus solar-generated electrons to slosh around in the middle of the day, I’d be more forgiving (so long as they did most of their work when the energy was basically free). But ending coal burning is priority number one in our fight for a livable future. A crusade against these voracious likeness-machines might just be necessary to save the Earth.

I think there’s plenty of interesting and creative use cases for generative AI. Let these models identify tumors, fold proteins, and analyze satellite data. I’m happy to live in a world where people can use software to generate stock visuals or jokey meme images or bad gimmick poetry or cover letter templates, so long as we can manage the energy costs and keep real human creatives supported. (If the AI industry is really worth $10 trillion like they claim, is it too much to ask that 1% of that be set aside and used as arts grants? $100 billion would feed a lot of starving artists.)

But I struggle to understand why we need to participate in the anthropomorphic fictions tech companies seem determined to slather on top of their models. Why should the rest of us have to indulge Sam Altman’s apparent Her fetish?

There’s something grotesque about this recent crop of so-called “artificial intelligence” technologies. It’s not that I fear runaway superintelligence, and it goes beyond the frustration that capital will use AI to squeeze and hammer labor. It’s that the goal seems to be to harness everything that’s good about humans (our creativity and personality and knowledge and expressiveness) while cleaving away everything that’s inconvenient: our needs, our frailties, our opinions, our self-determination.

Real people are messy, and there are forces that would prefer we were reduced to or replaced by abstractions instead. But I like real people. If you ask me, working through that mess to make a world together is what’s most exciting about being alive.

To be clear, I’m not necessarily signing up for the Butlerian Jihad party myself. I’m still agnostic on that front. But I want them at the table. I think a strong anti-AI position with the Butlerian credo at its core would be a valuable part of the discourse. It would force everyone to clarify their arguments about exactly why all this is necessary, or useful, or good.

The Butlerian Jihad is also the answer to this claim that “the genie is out of the bottle” and we have no choice but to accept these products. There’s lots that we could do that we have chosen, collectively, to try to forbid. Slavery, for instance, or child marriage, or incest, or various war crimes and weapons of mass destruction. We’ve made these choices because of a combination of practical and moral considerations. None of these prohibitions are baked into human society; they were won with organizing and argumentation. So we could, if we chose, put the genie back into the bottle — or at least chase it out of our homes and workplaces and platforms.

If we do go ahead and fill our world with tirelessly chipper, flirty, playful anthropomorphic AI voices, we should be prepared for what that will do to us, particularly children, the elderly, and the vulnerable. My friend Jay Springett had an excellent post the other week tying GPT-4o to Tamagotchi and other digital products that generate attachment by simulating aliveness. Many people have fond memories of such toys, and already our capacity to feel companionship with alive-like machines is being used to manage loneliness in elder care. He concludes that:

Any thought of regulation is going to have to strike a balance between utility and the very real emergence of emotional connection. As I said earlier, issues that arise from these tools – even with the capabilities as they are right now – might dwarf the downstream negative effects of social media

Indeed. Exactly why I’d like to have a real, principled, morally nuanced debate about this stuff. Let’s start by balancing the teams. Let’s up the Butlerian Jihad.

A coda: when we articulate the principles of such a Butlerian campaign, we might consider including another line from that hugely rich Dune glossery. In the entry on the ORANGE CATHOLIC BIBLE, which in the far future mashes together all the world’s religions, it describes the Accumulated Book’s supreme commandment: “Thou shalt not disfigure the soul.”

New Fiction: “The Concept Shoppe: A Rocky Cornelius Consultancy”

In case you missed the missive I sent out a few weeks ago: I have a new short story out. “The Concept Shoppe” is a sequel to my 2023 story “The Uncool Hunters,” with fast talking consultant Rocky Cornelius returning to take on such psychoeconomic future complexities like meta-experience, meet-cutes, and the secret desire of all Angelenos. Let me know what you think! You can give it a read and/or listen in Escape Pod.

Updates + Appearances + Miscellany

“An Omodest Proposal” — Contract signed, so I can regretfully inform you that I have entered into the Omelas Response Story Discourse. Look for this flash piece coming eventually in Lightspeed Magazine. Apologies in advance for this one!!

Speculative Insight — Check out this very cool publication featuring essays exploring themes and ideas from SFF. Among a variety of other thoughtful pieces, they have reprinted my essay “Space is dead. Why do we keep writing about it?”

Nebula Conference — Later this week I’ll be at the Nebulas this year in Pasadena. I’m taking it easy at this conference, just attending whatever looks interesting and chit-chatting with folks in the genre. If you’re attending, do send me a ping; I’d love to say hi!

Recommendations + Fellow Travelers

At the aforementioned C2 conference in Montreal, I got to hang out with fellow combo author+futurist Madeline Ashby, truly one of the sharpest, most interesting people at this particular intersection. Madeline has a new novel coming out in August, Glass Houses, about a tech startup’s company retreat gone mysteriously wrong. From what she told me, it sounds really great, so I gave it a preorder. You should too.

Also at C2, I got to meet Patrick Tanguay, futures-thinking generalist and curator of the very good Sentiers newsletter, of which I am an avid reader. It’s a great way to keep up with developments in planetarity, climate, AI, and so on. I recommend signing up!

Also also, I got to hang out with Nicolas Nova, an anthropologist and design researcher who co-founded the Near Future Laboratory. Nicolas had very smart things to say about AI, and a variety of other topics that came up over the course of a couple dinners. So check out his work and give him a follow!

Art Tour: Space Shuttle Still Life

In Montreal I visited the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, and saw this tremendous piece by Mark Tansey, Action Painting II (1984). I love the sense we get of being stuck, fixated on a scene that seems dynamic but has in fact hung around long enough for a lawn full of painters to capture it in perfect, still life detail. The scene is inspiring and humbling at the same time.

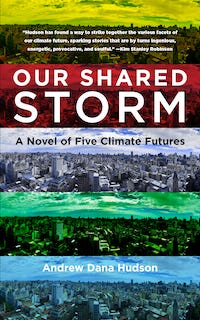

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my climate fiction novel Our Shared Storm, which Publisher’s Weekly called “deeply affecting” and “a thoughtful, rigorous exploration of climate action.”