This coming week I’ll be giving the first lectures in the PhD course I’m teaching here at LTU, Approaches to Futures. PhD courses are quite different in Sweden, often deployed as intensives over scattered, irregular weeks, rather than fitted rigidly into semester schedules. So making this class happen has been very dynamic, as we used to say at ASU.

Anyway, the course is going to be a survey of various ways of thinking about the future/futures, slightly tailored to my expertise. We’re going to cover foresight methods and scenarios, then look at design fiction and sci-fi prototyping. We’ll take a deep dive on cli-fi and solarpunk, and tour a handful of regional and diverse futurisms. We’ll finish on pace layers and far future eschatologies. Through all this I’m hoping to impart a rounded sense of future thinking to a group of researchers who mostly study highly technical energy technologies or system models.

I’ve come to refer to thinking about the future as a “wicked fun problem.” (We’ll see how the Boston joke lands with my Swedish/Indian/Iranian students.)

It’s a wicked problem because the future is a kind of history, and history is a unique, poorly bounded, complex and even chaotic system. History shaped by human perceptions and values, as well as vast socio-technical forces we struggle to control and ecological systems we don’t fully understand. History is defined by changes, upheavals, revolutions, and black swans. When we learn about the past, we spend at least as much time talking about the events that were sudden and unpredictable——wars, pandemics, assassinations, disasters, political upsets, market crashes, iconoclastic leaders and culture makers——as we do learning about the trends that were gradual, rational, and predictable.

We face enormous sense-making challenges when we try to understand history, and that’s when we already have the outcomes to kinda sorta help us make parse things. The future will have pretty much all those same chaotic factors plus new ones as civilization increases in complexity and connection, as technology advances and churns, as cultures mix and evolve, as the climate shifts in sudden and unprecedented ways. Predicting the future is a fool’s errand.

But thinking about the future is also great fun, because it requires/allows us to mentally step out of the world that we know, the world that constrains us and forces us to keep being who we presently are, and instead imagine and pretend that things could one day be different. The essential question is not “what will” but “what if?” There is a reason why even in button-downed, policy-oriented forecasting, most methodologies involve creativity, subjectivity, and interactivity. Most qualitative foresight methods, when done right, seek to put participants at ease, ask them to set aside their assumptions, and embrace open ended (though often still constrained) questions. There are quantitative methods that try to minimize the need for this, but most everyone agrees that, for all the above wicked reasons, purely quantitative approaches to making sense of and talking about the future are limited in effectiveness and scope.

More than anything I think of futures work as a form of play. And as those with kids know, play is not exactly fantasy. When children play they don’t just pretend their desires are met. They create play rules and try on play roles and imagine, briefly, a world in which those make sense. Kids will say things like “what if you chased me, but not like that you have to crawl like a bear, because the witch turned you into a bear.” That, to me, is much the same as a futurist saying “what if we had self-driving cars but they had to be totally transparent because too many people were using them as cheap housing.” Or a sci-fi writer saying “what if aliens arrived but they were only interested in whales.”

This is why when it comes to matters of the future, novelists——those odd creatures with inscrutable creative impulses, working in a tradition that predates modern rationality, who spend long days in conversation with made-up characters——are often looked to as experts. That doesn’t happen in many other fields. You don’t see novelists called in to offer their opinions on building inspections, battle plans, or medical diagnoses. But when it comes to the future, the ability to string together and organize a large number of hypotheticals, as speculative novels tend to do, is a core competency.

This is not just to toot my own horn but to argue that thinking about the future is a problem that’s both hard and fun at the same time, hence “wicked fun.” And it’s a task where the best efforts are often just as playful as they are rigorous.

Personal News

It feels a bit odd, since we only just got here to Sweden, but I can now say with some certainty what comes next for me after this project wraps up at the end of July. I’ll be headed back to AZ to start an MFA in creative writing at ASU. I hemmed and hawed about it for a few years, but last fall I decided that an MFA——a terminal degree that would let me teach, and a chance to keep growing my craft——was a good next step for my career. I applied widely, but in the end going back to our friends and family in Phoenix made the most sense. ASU has a great, fully funded program that embraces the speculative, which is exactly what I’m looking for. And better still, I’m told the admissions committee was excited by my work, and I believe surrounding oneself with people and institutions that pick up what you are putting down is a secret trick a long and successful career.

Art Tour: Solar Egg

A few weeks ago I visited the green industry boomtown of Skellefteå for a kickoff workshop of the project I’m here working on. There I paid a visit to The Wood, one of the world’s tallest timber buildings, home to both a hotel and the local library/cultural center. It was also, on the week I was there, hosting the Solar Egg: a golden, egg-shaped sauna created by the artist duo Bigert & Bergström. To my luck there had been a cancellation that morning, and I was able to take a turn inside, sweating it out with a bunch of Swedes, who followed the sauna’s prompt to talk about climate change.

Having never been in an art sauna before, I’m not entirely sure what to make of the experience, other than to appreciate the elegance of the design and hope that we can keep making beautiful things that nudge us toward a more sustainable world.

Material Reality: Ice (Hotel) and (Solar) Snow

This past month C and I made a brief excursion north, into the Arctic Circle to the mining town of Kiruna. It’s an interesting place, home to one of the world’s largest iron mines. The mine has destabilized the earth under the western edge of the town, and so the community has embarked on a multi-year process of evacuating that area, building a new city center, and moving key buildings to a safe distance. The difference between the doomed old center and the bustling new center is palpable at a jarring, vibrational level.

Not far from Kiruna is a place called the Ice Hotel. There are a couple of these in the world now, in far northern climes, but this was the first. It’s exactly what it sounds like: a hotel made (partially) of ice, featuring ice art, with a bar serving cocktails in little square ice goblets.

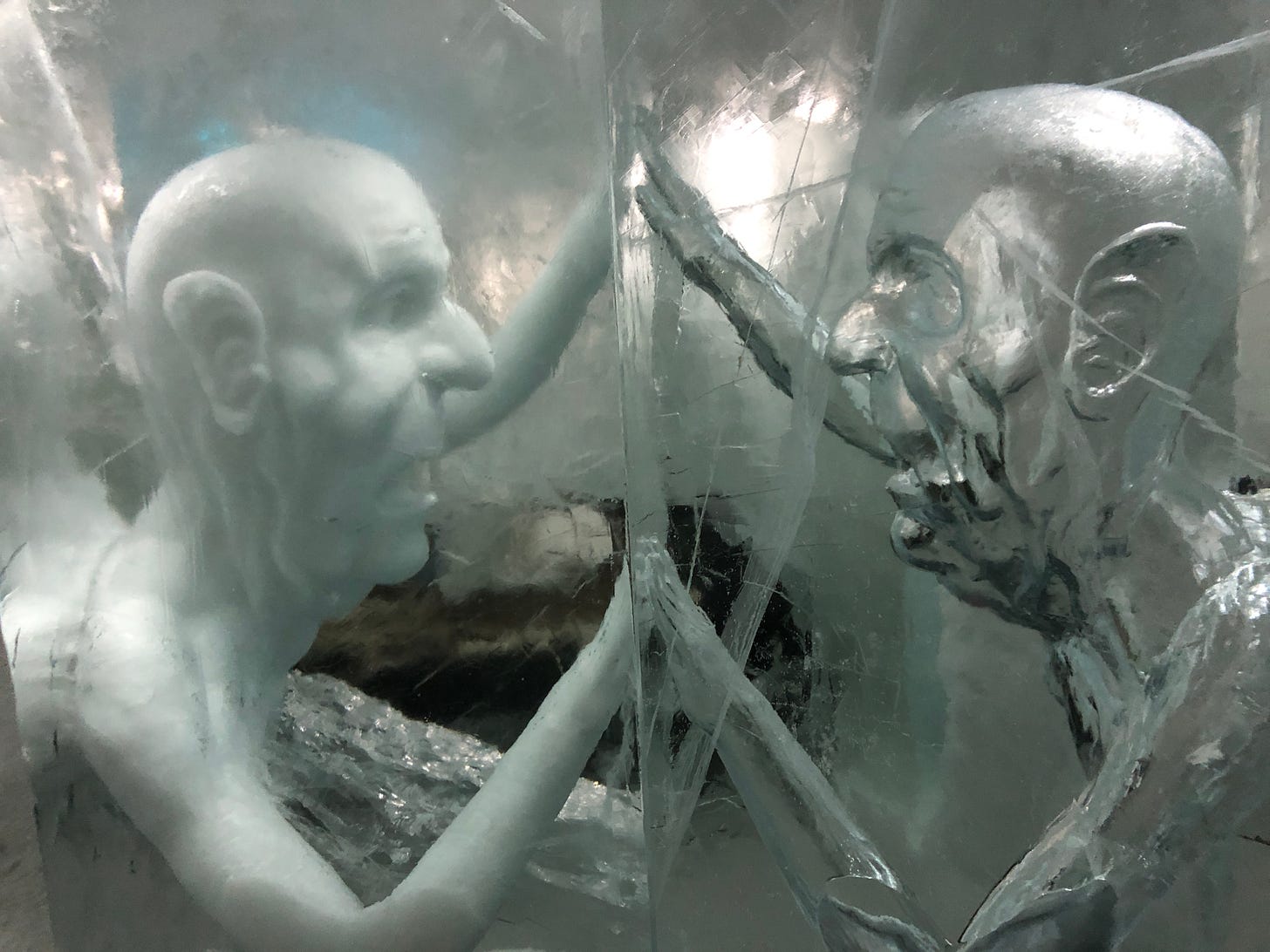

Figuring we’d never get a chance to do something like this again, we went, spending one night in their “warm” normal cabins and one night in a room made of packed snow on a bed made of a big clear block of ice. Meanwhile we explored the art rooms, full of ice sculptures that were weird, whimsical, occasionally freaky, often doing things I didn’t know one could do with ice and snow. I mean, just look at this.

Sleeping in the ice room was cozier than expected, thanks to the high end sleeping bags and ample advice the hotel provided. You hardly feel the cold, except as a pleasant nip on your nose. Well insulated, your body, that little chemical furnace, is more than up to the task. The room was very quiet and very dark, but not pitch black. Starlight and moonlight——and aurora light, for that night we saw a lovely, colorless swirl in the sky——somehow trickled through the meter-thick roof of packed snow.

My friend Mary Thaler told me a fun snow fact: “to have good snow for building snowhouses, you need to have had at least one blizzard. The reason is, the wind knocks off the points of the snowflakes, so they can lie more compactly. The corollary is, people who live in snowhouses in winter need to survive at least one storm in their tents each season. Which has got to be tough.”

Another fun snow fact is that the Swedish word for “snowflake” translates more literally to “snowstar,” which I think is just a superior term.

Snow is still everywhere in the north, even here below the circle in Luleå. Occasionally I get off the bus to find the afternoon sun shining from one half of the sky while snow drifts down from the other half. I’m learning to tell the crunchy, friction-giving powder that’s nice to walk on from the fresher, finer deceptively slippery snow-dust that can send one sprawling. Riding around town I’m occasionally struck by the medians and fields where the snow is still virgin, unbroken, un-trod upon white. Somehow I find it odd to see such vivid confirmation that there are places in the middle of busy cities where simply nobody walks.

I feel compelled to write, again, about the snow and ice, because I know by the time I send out my next missive, on May 1st, it will probably be gone. The days are getting longer, and fast. Most of this week the midday will get above freezing. I’ve indulged in a few “Lands of Always Winter” jokes since moving to Sweden, but really, the “always” is on notice. I took a short trip to Stockholm, and walking around there, free of snow and ice, wearing just a light jacket, I was reminded that in most places mid-March is simply chilly.

Oddly, I find myself a bit anxious about the prospect of proper spring. Maybe it’s just my Arizonan dread of summer kicking in, but I don’t think so. So much of the city is buried under snow, I feel a bit like melting all that will make it a stranger to me again. The snow seems like a glue that holds the world here together.

In interesting, and solarpunky, detail is that the snow reflects enough sunlight to give some juice to properly oriented photovoltaics. Not surprising, given “snow blindness” has long plagued arctic explorers. Solar here in the north might seem like a poor investment, given the long winter nights and the glancing angle of the sun. But PV is so good now that you can still generate a respectable number of electrons during all but the darkest midwinter weeks. The whole affair takes on a fascinating seasonal dimension, with big energy surpluses possible in the height of summer.

The question is: where to put the panels. I like the idea of moving them. In the winter, you put them on your south-facing walls, stood up vertically so they don’t get covered by snow. You catch the low sun and also the photons bouncing off the snow. Then, when spring arrives and everything melts, you move your panels up onto your roof. Heck, why not make a day of it? A seasonal festival, even. Everyone could get together with their neighbors on the first real, snow-free Saturday, have a cookout, and haul panels up on roofs. Come fall, they could do the reverse, while sharing the last of the sun-swollen harvest.

There is a big push, pretty much everywhere, to make the new, renewable energy system as invisible and hands-off as the old, fossil energy regime. A part of me kind of suspects that this would be a mistake, or, at least, we’d be missing out on an opportunity to have a deeper, more meaningful engagement with the energy we use. Not in a punitive, calorie-counting, rationing sort of way, but more of an appreciative, slow food, abundant way.

Maybe my communitarian vision above is too granola, naive about the technical skills required, now and forever, to get solar PV properly wired and mounted. People won’t want another chore, won’t want to have to plan their modern lives around fickle things like the weather and other people. They’ll just want to flip the switch and get light, no thought required. But, like so many things, we won’t know what we’ll really want until we’ve had a chance to try it another way.

Andrew, I am enjoying reading about your Swedish adventures. What great experiences.

Good to know what your future entails, too.

Ann S