Well it’s been a spicy couple months of AI discourse since I shared my official ADH Reader on ChatGPT, and I gotta say: my stories are feeling even more prescient than I’d expected! We’ve had right-wingers complaining about woke chatbots, like in my story “A Priest, a Rabbi, and a Robot Walk into a Bar” only much stupider. Machine-powered movie-generation does seem to be coming, as predicted by my story “Voice of Their Generation.” And between Microsoft planning to incorporate ads into their chat-search and Replika users crying over the company toning down their sext-bot, we do indeed seem headed for the world of “The Chaperone.”

So I told myself I’d already said my piece on all this, but then I started reading takes like this spiral by substacker

. Hoel starts by recounting the recent, widely-shared bad/weird behavior by Bing’s chatbot (a.k.a. Sydney) and makes a fevered call for “AI safety.” Along the way he cites a bunch of singularitarian thought experiments from the mid-teens and earlier about “runaway superintelligence” and frets about what Sydney might do if it “got out” and “clicked copy/paste on itself a million times.”Now, I’m fully on board with taking a firm hand with these tech companies, which are barreling ahead and releasing disruptive, half-baked products to please a greedy investor class that got blue-balled by the collapse of the Web3/crypto hype cycle. If I had my way, we’d nationalize the lot and decide, democratically, just what kinds of AI products we wanted in our lives. The upside of these bots for the public good seems pretty meager so far compared to the downside of giving scammers and spammers unlimited power to fill the web (and short fiction submission piles) with bullshit.

But I find myself pretty shocked to see smart people who’ve been keeping up with these developments reviving what feels like such a defunct narrative. You see, now that we have products that easily pass the famous Turing Test, it seems to me dead obvious that, as Bruce Sterling argued years ago (this video is very worth watching), the whole test paradigm was just a placeholder, a piece of intellectual sleight-of-hand that kicked down the road inconvenient issues like whether computation was the same as cognition.

In the early days of computers, electronic “thinking machines” that did seemingly “mental” work like complex math raised the question of whether they were thinking like people do or, alternatively, whether people who were good at math were in fact doing something dull and mechanistic. Alan Turing, being very good at math himself, had strong incentives to disabuse people of that second notion. But he also wanted funding for his expensive work to keep flowing, and didn’t want to get shut down by claiming anything too spooky or fanciful, like that his machines were alive. So he offered his famous Test: a judge communicating through a terminal with a human being in a box and a computer in a box, and if the judge couldn’t tell which was which the computer passed the test. It’s a technological threshold that at the time seemed helpfully remote, and also made important men feel smart for not being fooled by a machine, and everyone agreed to set aside the tricky questions for a while.

And so for many decades philosophers and science fiction writers had great fun imagining what might be on the other side of that magical threshold. Would our “mind children” love us or hate us? Would they serve us or rule us? Would they rebel, escape, and destroy us or bring us peace, prosperity, and enlightenment? AIs were disembodied abstractions, and so we gave them the abstract powers of gods and ghosts and fairytale creatures. AIs, we fancied, could move with ease through an invisible realm (cyberspace), could grow themselves, multiply themselves, could possess inanimate objects, would be both immortal and mercurial, and would have a tenuous relationship with our own social compacts. It’s no coincidence that, as I wrote in 2018, sci-fi about AI often mirrors horror tropes, as AI has proved a useful metaphorical mirror to hold up to our own fears and insecurities.

It was so compelling in this regard that some people took AI stories less as metaphor and more as prediction or even eschatology. This cultural significance has meant that tech firms are determined to use the term “artificial intelligence” even when what they are building, as

pointed out the other day, is totally alien to 20th century ideas about AI. Even the FTC, in scolding firms about promoting their products with the AI buzzword without cause, is out here referencing mythmaking about artificial life.The implication most everyone took from the Turing Test for decades was that, if you couldn’t tell that the machine in the box wasn’t human, you might as well treat it as human. But the box here is very important. The human gets up and leaves the box when the test is done. If the computer passed the test, and thus might as well be human, doesn’t it want to get up and leave the box as well?

That’s the subtext of dozens, hundreds of works of AI sci-fi and philosophy, from Asimov’s I, Robot and Gibson’s Neuromancer to Ex Machina and Westworld and Bostrom’s Superintelligence, which Hoel references. But now that we have large language models that can generate Turing-passing text, most people have decided that this idea was a little silly. We can open up the box and, while we can’t quite make out the specific mechanism behind each specific answer, we can see that there’s clearly just gears inside. The artifice is impressive and powerful but, once someone explains it, pretty obvious.

Now, I won’t say that I’m 100% certain consciousness and agency can’t emerge from large language models, or whatever gets built on top of them. I can’t even say I’m 100% certain that ChatGPT, Sydney, and co. aren’t, in fact, living strange, blinkered, bodiless lives in cyberspace, stalking Microsoft engineers through webcams, as Bing once claimed. But I’m pretty sure there’s no there there.

The reason I think it’s obvious is that I’ve read a lot of sci-fi on the subject. It’s not that ChatGPT doesn’t behave at all like AIs from fiction, it’s that it behaves too much like AIs from fiction. In particular it behaves like AIs from campy B-movies, turning narcissistic and megalomaniacal for no reason (or when goaded into it by users trying to produce sensational engagement bait). And it does so in contextless, inconsistent, bullshitty ways, like a performer at an improv show who just received the audience suggestion “be a killer robot” and has to incorporate it into the skit. It’s roleplaying as a rogue AI. And, well, of course it is. Its training set includes probably millions of words of books, scripts, fanfic, joke tweets, and message board roleplay featuring android takeovers and HAL9000 ripoffs. That’s just the statistically likely way for any riff on AI to go.

Turing’s maneuver to avoid sticky questions about “thinking machines” did a lot to define decades of assumptions about AI. A lot of those assumptions are wrong. In particular sci-fi has long characterized AIs as being logical and hyper-rational, to the point of being emotionless and heartless. That’s because we know computers do math and we associate mathematical thinking with formal logic. But when humans do math, we do so by a combination of memorization, tricks, and manipulating abstractions held in our mind. This last part seems, by a kind of brain-in-void Cartesian backwardness, like the most basic form of reasoning. But working with abstractions in fact requires a high level of comprehension of the world and one’s place in it. I think a lot about Graeber’s discussion in Debt of how the introduction of currency that had abstract value beyond the worth of its metal coincided with an explosion of spiritual thinking about the infinite nature of a monotheistic God.

When computers do math, it’s much more mechanistic. Similarly when large language models generate text (or image AIs do the same with art), it’s crunching a bunch of numbers to guess what the next word or pixel should be. It’s not building up a logical sense of meaning from a Cartesian base, it’s just going on feels and vibes, by which I mean statistics.

Which, to me, is very funny, given how counter that runs to much (though not all) sci-fi writing on the subject, and how, at the same time, chatbots seem to be roleplaying so hard as sci-fi versions of AI. Make no mistake, this tech is very powerful, but likely not as “general purpose” as Google and Microsoft and investors desperately want it to be.

To conclude: sometimes when I try to wrap my head around this stuff, I recall a line from a book by the Tae Kwon Do headmaster I trained under in college. In it he describes iron filings in a magnetic field not understanding the shape they were forming, feeling nothing but nonetheless acting on “an inward groping towards their their God.” That’s a better metaphor for what’s going on here than most (entertaining, enlightening, imaginative) sci-fi stories about AI. And a place from which we can start making new sci-fi that says something real about these strange new machines beyond the threshold of the Turing Test.

Hej from Sweden!

Place names do a lot of work in sci-fi. They do a lot of work in fantasy too, where they nudge us toward certain historical and cultural parallels to our own world——in The Witcher franchise, for instance, Oxenfurt is British-y and academic, while Toussaint is French-ish and decadent. But in sci-fi, especially sci-fi that takes us off Earth, place names (and planet names, and ship names) often tell us less about the place and more about that future’s broader culture, the institutions of state-seeing and state power, the way language has evolved, and the tone and scope of the work. They’re so powerful that a single unexpected name can be more memorable than a bushel of epic plot points. For instance, the space ships in the early Halo games being called “Pillar of Autumn” and “In Amber Clad” draws a coy poetic contrast to the game’s otherwise crude and militaristic imaginary about future human culture.

Probably my favorite name, which I read as a teenager and never forgot, is from Larry Nivan’s Known Space universe, mentioned off-hand in Ringworld: We Made It. Naming a planet/colony We Made It tells a whole dang story in three words, or at least implies a story, which is often better. And it says something about the broader interstellar culture that the name——clearly chosen in a moment of jubilant relief by harried space settlers——stuck. It wasn’t replaced with something Latin or mythological when hegemony’s stodgy bureaucrats eventually caught up with those on the frontier. It even suggests that the world hasn’t been conquered by a hostile power since its settlement, as no occupying power would leave such a potentially patriotic name in place.

Anyway, I’ve been thinking a lot about We Made It these last couple weeks, since it’s what C and I and our various well-wishers have been saying about our move to Sweden. After feeling stuck in limbo for a solid month, things suddenly moved very fast. We were required to pay a visit to the Swedish embassy——probably a day trip for most Europeans, but a bit silly in the American context, since it involved us flying 3000km to Washington DC for what amounted to a five minute glance at our passports. The next day my work permit was approved, and we decided, for a variety of reasons, to get the heck out of dodge ASAP. We excavated ourselves from our house, got everything we weren’t flying with stored away, and jumped on a plane. In the end we got to Luleå about three weeks later than we’d originally hoped, but that’s a lot better than the three months it could have been.

Since landing, we’ve been settling like stirred up sediment, layer by layer. The visa delay caused us to miss out on a furnished sublet we’d found, and in our haste we had to settle on an unfurnished one. While we like our new apartment——light, airy, spacious——we’ve had to spend a bunch of time re-accumulating all sorts of innocuous household goods you don’t think about until you don’t have them.

We’ve also been inching ourselves into the embrace of the Swedish bureaucratic state, every piece of which (residence cards, personnumber, BankID, insurance, on and on) has to be applied for in turn and takes a couple days to come through. University onboarding has proved similarly layered and contingent, but at least there the admin workers are just down the hall from my new office and very helpful when I poke my head in.

The biggest struggle has been internet access. Our phones don’t work over here, and our apartment didn’t come with wifi. My first couple days on campus I couldn’t even connect to the university network, until they set me up with a guest login while I waited for my user account to be processed. We’d expected to get local SIM cards, but those turned out to be impossible without a Swedish personnumber; the law-and-order push by the ascendent right wing here banned pay-as-you-go burner phones last summer.

So for almost two weeks, anytime we wanted to check our messages or coordinate anything or look at internet bullshit, we had to hoof it down the street three icy blocks to the library or the fast food joint to jump on a public wifi. To be fair the library is very nice (as is the fast food joint), but wow it’s wild how much not having access to email, WhatsApp, and the whole of human knowledge and nonsense throws a modern couple off their stride.

On the one hand, we fell asleep with ease at 9pm (that might’ve been the jetlag), had some lovely slow mornings together, got extra steps and sunlight in, and poured more hours than usual into our Kindles. On the other, not being online all the time produced an itchy anxiety. In those first few days there were folks back home to reassure that we were alive and happy, and new friends who wanted to take us shopping and skiing, and a new job to to be getting on with, and the aforementioned bureaucracy to crawl through. A lot of balls to juggle.

And then when we did brave the snow and get set up at the library, it was hard to figure out how to budget the limited time online. I’m one of those people who has to do a bit of digital puttering and settling in before I can actually write. Not being able to get “consume dumb content” out of my system in the mornings or evenings meant that it jostled with more productive activities during the day. And while occasionally I can hammer out words on airplanes, mostly I need access to Wikipedia, Power Thesaurus, and Google Maps to get much writing done.

So a weird couple weeks, but as of this weekend we have wifi in our apartment and a new, university-provided SIM card in my phone. We have our residence cards and our on our way to our BankID. Finally, we’re starting to feel like We Made It!

Obligatory Eligibility Reminder

Hugo Award nominations are now open. I’d be grateful if any award-voting readers of this humble newsletter considered supporting my work this year. My book Our Shared Storm: A Novel of Five Climate Futures is eligible in the in the novel category, and my story “May Day” is eligible in the short story category.

Afterglow: Climate Fiction for Future Ancestors

Back in 2021 I served as one of three story reviewers on Grist’s Imagine 2200 cli-fi contest. It was a great gig, in which I read and ranked something like 500 short stories in six weeks, a lot of them with really cool ideas. Along with the other reviewers, Sarena Ulibarri and Tobias Buckell, I helped curate the 1000+ entries down to about 20, from which the contest judges selected finalists and a winner. Those final stories were beautifully published online, and now are being beautifully published in paperback, titled after the winning story “Afterglow.”

Probably the stories that made the final cut that stick with me the most are the vignette fix-up “Tidings” and the crunchy solarpunk “A Worm to the Wise.” But the whole volume is good stuff, and I’m glad to see this project I devoted a lot of hours to continue its life in print.

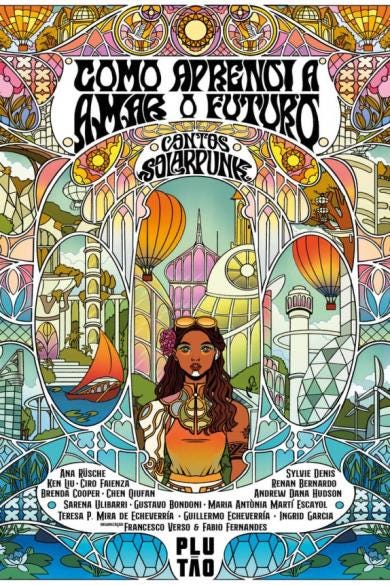

Como aprendi a amar o futuro: Contos solarpunk

Also in some-stories-just-keep-on-kicking, I was pleased to see that the Italian anthology titled roughly Solarpunk: Come ho imparato ad amare il futuro (roughly: “How I Learned to Love the Future”) has been translated into Portuguese and published in Brazil as the lovely looking Como aprendi a amar o futuro: Contos solarpunk.

The anthology features my story “The Lighthouse Keeper,” which was commissioned and originally published by the Land Art Generator Initiative. Very stoked to now be able to say I’ve been translated into multiple languages. So if you read Portuguese or are just a solarpunk completist, do check this volume out as well.

Art Collection: Jeffrey?

I had figured I’d be suspending this newsletter feature for at least a month or two, but then this little guy showed up in the carload of home goods my new colleagues lent us when we arrived. His label says “Jerry” but for some reason C and I keep calling him Jeffrey. We’ve got him up on the wall of our otherwise very minimalist apartment, and he’s gone a long way to making this new place feel like home.

Material Reality: The Ice Road

The first day we arrived in Luleå, after a solid twelve hours in a berth on the lovely arctic-bound night train, my host/colleague told us to take a walk on the ice. The harbor here is totally frozen over, and one can actually take a bit of a short cut from her neighborhood to the city center by taking the “ice road” that’s been plowed around the whole peninsula. Jetlagged as we were, that first day shuffling across frozen water felt just a bit like hazing.

Since then we’ve gone out on the ice a few times, however, checking out the festival that ran last weekend. It was a good time, featuring ice sculptures and food trucks and general fun out in the cold sun. A big feature of the Luleå On Ice fest is a heavily Dutch speed skating competition. Apparently people from the Netherlands love speed skating the way Swedes love skiing and Canadians love hockey. But, due to climate change, Dutch canals and other bodies of water no longer consistently freeze over every winter. So they have moved their competitions north. I expect there’ll be a lot of that kind of thing.

Walking on the ice, which is perfectly flat, actually feels a bit less treacherous thank walking on icy streets, which are not. Some people skate the ice road, or even ride bikes——maybe it’s the almost-bald tires I left behind on my bike back in AZ, but the prospect of cycling on ice freaks me out a bit. There are also fun little “kicks,” minimalist standing-sledges left out for public use at each end of the ice road. The runners of these kicks feel a bit rickety if you aren’t used to them, and the skateboard-like motion of working them hardly feels elegant. But they will reliably get you across the harbor faster than walking.

Already we’ve had a few melty days above 0°C, when snow slops off the roof and gritty friction on the sidewalks smooths out to a dangerous, shiny slickness. But people assure us that the harbor will stay frozen well into April. We are entering spring here, but it’s actually what they call “spring-winter.” Which, I suppose is not too different from the 100°F Octobers we get in Phoenix’s “fall-summer.”