Why do we trust novelists with the future?

Three theories, five charts, and the Reverse Anna Karenina Principle

This past week I had the pleasure of being invited by the singular Julian Bleecker of the Near Future Laboratory to give a ‘super seminar’ on the relationship between fiction and the future. I was joined by the amazing sci-fi writer and futurist Madeline Ashby.

In his emails promoting the event, Julian described once joining a technology lab and, upon asking for the lab manual, being handed a copy of William Gibson’s Neuromancer. "A science-fiction novel? That's the "manual" for this laboratory?” Julian reports thinking. “What the heck..?"

The question of why sci-fi novels have an odd sort of preeminence in the world of futures thinking also came up in the Approaches to Futures course I taught back in Luleå. Given that strategic foresight is its own decades-old discipline, and there are professional foresight experts who work with governments and private industry, why are sci-fi novelists often considered experts in the future?

Novelists, those strange creatures that bury their points in ungainly, hundred-thousand-word narratives, rather than communicating, the way normal people do: with slide decks. After all, we rarely conflate authors of mystery novels with actual detectives, or authors of historical fiction with trained historians. (Not to minimize the research it takes to write a good pice of historical fiction.) And yet, we often look to sci-fi novelists to tell us about our future.

I have three big ideas/theories about this question. First, and most straightforwardly, I’d argue that fiction writing and futures thinking share core competencies. (This applies even to non-speculative fiction.) Both involve assembling big piles of hypotheticals and putting them in a convincing, compelling order. Both are a kind of imaginative play, throwing aside familiar norms and trying on new ones, like children in games of pretend. And both involve contending with the endlessly complicated system dynamics of human society. As the mid-20th century literary critic Lionel Trilling argued,

“Literature is the human activity that takes the fullest and most precise account of variousness, possibility, complexity, and difficulty.”

My second take is that sci-fi creates modern mythologies that give us ways to make sense of technological change. Consider the following chart from circa 1965:

This trajectory, from the pony express swiftly up the hockey stick to interplanetary and interstellar travel, was the presumed future of transportation for a while there in the mid-20th. This assumption was itself the product of science fiction, but it also inspired a ton of sci-fi (perhaps even most sci-fi, though I really have no idea of the numbers there). But dreams of space ships exploring the stars, of galactic empires rising and falling, of meeting aliens and unlocking the secrets of the universe——these are all quintessential SF stories.

So quintessential that we are still telling them, despite the fact that the above trajectory hasn’t really come to pass. After the moon landing our speed ambitions scaled back, and we leveled off with the Boeing 747 as the best, most popular form of high-velocity human transportation. We’ve done little to achieve interplanetary/interstellar travel for a solid 50 years. And yet, you can go down to your local bookstore and pick up a freshly published space opera to read. Why? Because the mythology created by SF around the above chart still entrances millions.

Did we learn from our (so far) failed predictions of asymptotic progress? No, of course not, for there are other mythologies, spun around other dizzying technological advances. For example, The Singularity, which extrapolates the curvature of Moore’s Law all the way up to the heavens of machine divinity.

The Singularity is a mythology of humans playing God, making gods, and becoming gods. I’ve written before about how SF stories about machine sentience often don’t exactly line up with the so-called AIs we’re actually building. Nonetheless, this mythos is cultishly popular in many circles.

And we have other SF mythologies that dominate our media and give shape to millions of modern minds. Superheroes are arguably inspired in part by the sudden onset of modern medicine. Stories of apocalypse and post-apocalypse were necessary myth-making around the startling appearance of the atomic bomb. And now we are starting to develop a new mythology based around two new hockey-sticking charts:

What’s going to come of all that, I don’t know. My point here is to highlight the mythologizing function of science fiction, creating not so much predictive futures but ones to help us derive meaning in a changing world.

Finally, theory three: we turn to novelists to tell us the future because stories allow us to make judgements about worlds we might live in. There is one other big SF mythology worth mentioning, and that’s the social and economic mythology of dystopias and utopias. For me it all comes back to one last chart:

1973 is, for me, an epochal rupture in the development of modern technology. It marks the moment when technology kept getting better without actually bringing increased prosperity to most people. I think if you showed this chart to some of the Golden Age SF writers, they’d frankly find it shocking.

To me the opening of the alligator maw proves that civilization is not a simple function of its technology, riding a trajectory to some inevitable, lofty destination. We’ve made collective choices (or had them made for us) about how we order our society, and we have more choices to make about how we’ll do so in the future.

In her own talk, Madeline argued that dystopias largely share the same characteristics: poverty/inequality, oppression, disease, environmental ruin. “A jackboot is a jackboot is a jackboot,” she said, and I agree. Utopias, meanwhile, are rarely so clear cut, because visions of a good life and a just society are based on normative value judgements about which reasonable (or unreasonable) people might easily disagree. I.e., to choose one from The Discourse a while back, would you rather live in a communism that’s abolished restaurants or a communism where all meals are had in restaurants? And as Madeline argued in her own talk, one group’s utopia is sometimes another group’s dystopia.

I call this the Reverse Anna Karenina Principle:

“All dystopias are alike.

Each utopia is utopian in its own way.”

We have to choose to close the maw and avoid dystopia, and we also have to choose what kind of utopia we might want to live in. We turn to SF writers because stories of the future are powerful seeing instruments to inform these choices, as well as platforms for hashing out the necessary debates.

Art: “Looking for Hades” by Kilian Eng

Our new place is smaller, with fewer art-hospitable walls, but we’ve gotten up a few pieces, including our big print of this beautiful Kilian Eng piece. For some reason its new location has me looking at it differently, feeling the trepidation with which the tiny, central figures are approaching the cavern maw.

A Solarpunk in Congress

The other day Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was asked, on an Instragram livestream she was doing with her dog, about her take on climate doom. AOC replied that she was a big believer not just in climate optimism but in solarpunk. For those of us who started trying to “make solarpunk a thing” back in the mid-teens, this has felt like a big moment. It’s a thing now! It’s very much a thing. In 8-10 years we went from Tumblr posts to having a member of Congress identify with our cultural project. That’s not too bad!

All of which is to say, if you’re interested in learning more about how to take a cultural project from the extreme margins to the halls of power from someone who was there for most of that journey helping nudge it along, I’m open to consulting sessions. As is, I hear, my friend @thejaymo who has been a key advocate and shepherd of the movement. And if you’ve got ideas about what’s next, get in touch.

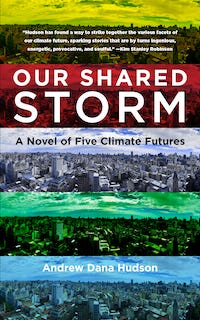

If you like the this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent climate fiction novel Our Shared Storm, which Publisher’s Weekly called “deeply affecting” and “a thoughtful, rigorous exploration of climate action.”